President Cyril Ramaphosa.

Non-government organisation Cape Forum has said that President Cyril Ramaphosa’s signing of the controversial Basic Education Laws Amendment (Bela) Bill on Friday is an indication of “school capture”, and that it would turn to the courts to stop the legislation.

The forum said on Thursday it urged “coloured communities” to not view the signing of the “draconian” Bill as something that would only affect “traditionally white schools”.

“This is a fight for every school and every household in South Africa and specifically the Afrikaans-speaking communities,” said the forum.

“Our experience so far is that many communities may take a never-mind attitude towards Bela because the ANC created the impression that it is only former Model C schools — in other words, traditionally white schools — that oppose it,” said Heindrich Wyngaard, the executive chairperson of the forum.

“However, we know that this is not the case, as traditionally coloured schools can also be forced by the legislation to adjust their Afrikaans language policy to accommodate small numbers of non-Afrikaans-speaking learners.”

Critics of the Bill unanimously view it as political interference in schools, saying that school governing bodies, and therefore parents, should not be undermined.

Lobby group AfriForum and trade union Solidarity have said they will approach the courts when the Bill is signed. ActionSA said on Wednesday night that it would also consider legal action if the Bill was signed into law. ActionSA has called the Bill “a power grab by the basic education minister”.

When it comes to language policy, the school governing body is in charge of setting that policy, but the Bill emphasises that this is not unequivocal, and the provincial head of the education department may “intervene” when there is what is deemed discriminatory language or admission policy.

The Bill was tabled by former education minister Angie Motshekga and seeks to amend the South African Schools Act of 1996 and the Employment of Educators Act of 1998.

Once signed it will be the purview of the new education minister, Siviwe Gwarube.

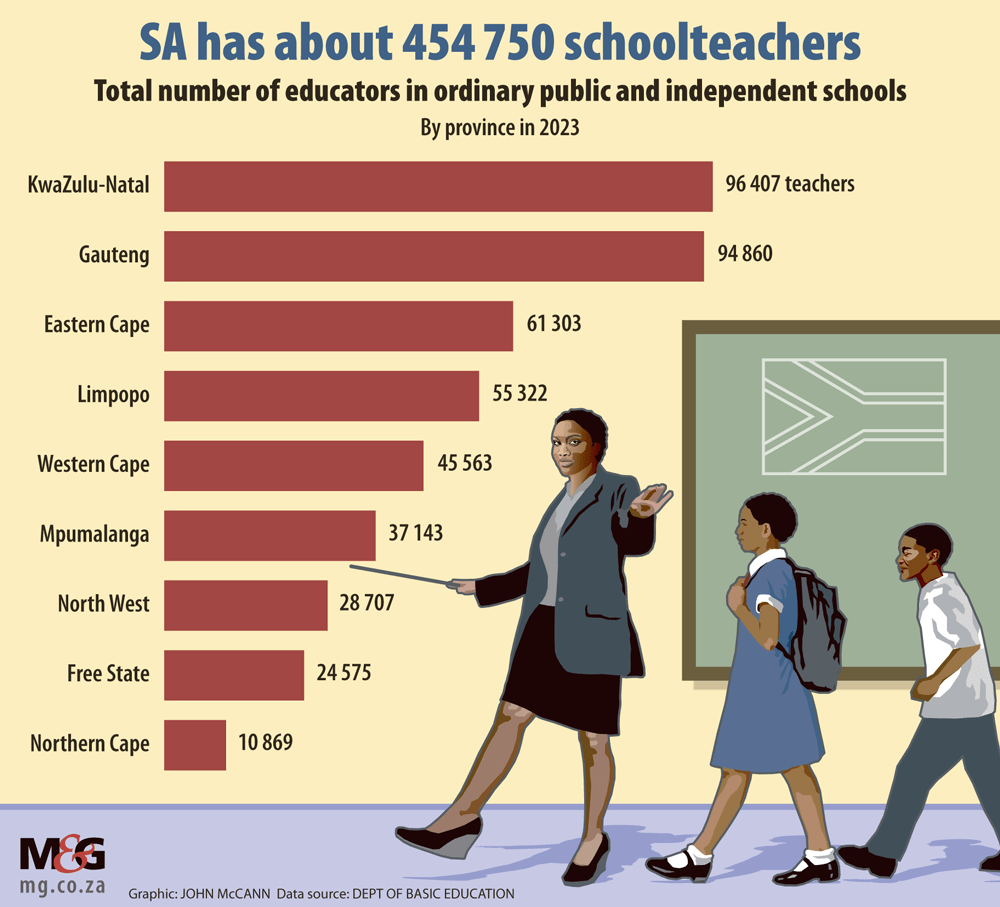

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

The Bill has faced staunch criticism from the Democratic Alliance (DA), with party leader John Steenhuisen accusing Ramaphosa of violating “both the letter and spirit of the joint statement of intent that forms the basis of the government of national unity”.

The DA wants the Bill to be returned to parliament “because it has constitutional implications for the right to mother-tongue education, amongst other issues”, said Steenhuisen.

Gwarube previously told the Mail & Guardian that she would adhere to her mandate and expeditiously implement “aspects” of the Bill should Ramaphosa sign it into law.

“The Bill is the brainchild of the department that I lead and so if the president signs the Bill then we have to get on with the business of governing and implementing it,” Gwarube said.

This comes in the wake of the Western Cape education department announcing that it plans to cut 2 400 teaching positions in January 2025.

But when the Bill is made an Act, it would require more teachers to be hired to implement certain aspects, such as making grade R compulsory.

In a statement after the announcement of the teacher cuts, Gwarube blamed the previous administration for “poor policy choices” which would lead to thousands of teachers being jobless.

“These fiscal challenges stem from years of poor policy choices related to the management of our country. To emerge from this situation, we must make sound policy decisions and ensure better management of both government and the economy,” Gwarube said at an urgent meeting held by the Council of Education Ministers last week.

In August, the Western Cape education department announced plans to cut 2 400 teaching jobs because of a severe budget cut of R3.8 billion.

The reduction in posts will mean that some contract teachers will not be reappointed after their contracts end on 31 December, and some permanent teachers will be asked to move to schools where there is a suitable vacancy.

The news about the job cuts led to an outcry from teacher unions, who threatened to take to the streets and file a case against the department and report it to the Education Labour Relations Council (ELRC) for lack of consultation.

“This will not be accepted because the department hasn’t consulted in line with the legislation and we have declared a dispute. The matter will be scheduled by the ELRC in due course,” said the South African Democratic Teachers’ Union secretary, Mugwena Maluleke.

The Good Party and the Western Cape legislature are scheduled to debate the matter on Thursday.

There is no indication of how many teaching positions will be cut in other provinces, which are set to announce the number of posts for 2025 by 30 September.

The Eastern Cape education department announced in a meeting last week with teaching unions that it plans to maintain 52 817 existing posts with “no retrenchments” for the next three years.

During the budget speech in February, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana allocated R324.5 billion to basic education for the 2024-25 financial year, with additional money to cover teachers’ salaries.

Previously, in February 2023, the treasury allocated additional funds to the provincial education departments to pay teacher salaries.

But, in the 2023 medium-term budget policy statement, the treasury acknowledged that budget pressures on education “could lead to larger class sizes and higher learner-teacher ratios, possibly resulting in weaker educational outcomes”.

Provincial education departments receive their Compensation of Employees budget allocation directly from the treasury, which is sent to the respective provincial treasuries.

Provinces then act as employers independent of the department of basic education. Each provincial education department is responsible for managing its own human resource matters in coordination with its provincial treasuries.

But, when provincial departments start to take the strain, the ripple effect is felt across the national system.

“This underscores the critical need for coordinated action to protect our education system,” read a statement by the basic education department.

In April, Motshekga said her department has started recruiting people to fill the 31 000 teacher shortage in the country.

KwaZulu-Natal, at 7 044, recorded the highest number of unfilled posts followed by the Eastern Cape and Limpopo at 6 111 and 4 933, respectively. Northern Cape, at 726, has the least number of unfilled posts.

This is a 28% increase on the 24 000 vacancies recorded in 2021.

When asked by the M&G whether the department still plans on recruiting temporary teachers, Gwarube said she was “still assessing the situation”.

A survey by the education department showed that, as of December 2023, 12 701 575 learners were enrolled in public schools with 409 488 educators in 22 511 schools across South Africa’s nine provinces.

In 2023, a study by Stellenbosch University found that public schools have an average of 35 learners to one teacher — the maximum class size for foundation phase learners (grades R to four).

Early this year, the National Teachers Union raised the matter of a primary school offering grades one to seven and operated with only two teachers — one of whom served as principal.

Gwarube, since the teacher cut announcement, said she would approach the treasury to find ways to protect the education system from “painful budget cuts”.

The Governing Body Foundation has expressed its support for Gwarube’s plan for the provincial education departments to analyse the effect of the fiscal constraints.

“National treasury may have to consider reprioritising expenditure to prevent the irreparable harm that would result from undermining the ability of schools to provide quality education,” said Anthea Cereseto, the chief executive of the foundation.