South African actor, author, playwright, director and grandfather of the nation John Kani is not going to follow the example of another John who returned his fancy medal to Buckingham Palace.

The other John — Lennon, that is — was made a Member of the British Empire (MBE) with the other three Beatles in 1965. Lennon gave his medal to his Aunt Mimi, who kept it on her mantelpiece, according to an article on Radio X’s website.

Four years later, on 25 November 1969, Lennon, who had decided to make a statement, had it fetched. He wrote a letter to The Queen on notepaper headed “Bag Productions”:

“Your Majesty,

“I am returning my MBE as a protest against Britain’s involvement in the Nigeria-Biafra thing, against our support of America in Vietnam and against Cold Turkey slipping down the charts.

“With love. John Lennon of Bag.”

Lennon’s chauffeur was dispatched with the letter and the medal to Buckingham Palace. The article says it was discovered decades later in the vault of the Chancery Department of the Royal Household in 2009.

There is no possibility that something like that will happen to our John — Kani’s — medal.

It is Tuesday morning, and we are meeting for coffee at the WAM Café at Wits to talk about him being made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire (OBE) and receiving his medal from the British High Commissioner Antony Phillipson at a formal evening ceremony held at his residence in Pretoria.

Kani is keeping his, he tells me.

“Apparently, before my announcement, there was a Jamaican musician or activist who was also to be honoured,” Kani tells me. “And he made this statement that, throughout his life, he’s fought the illegal occupation of this island and enforced cultural identity, imposed on them of being British, when he knew that he was Jamaican.”

It made the 81-year-old Kani pause. “But then I listened very carefully at the motivation. Then I thought, ‘Well, it is something I’ve done.’”

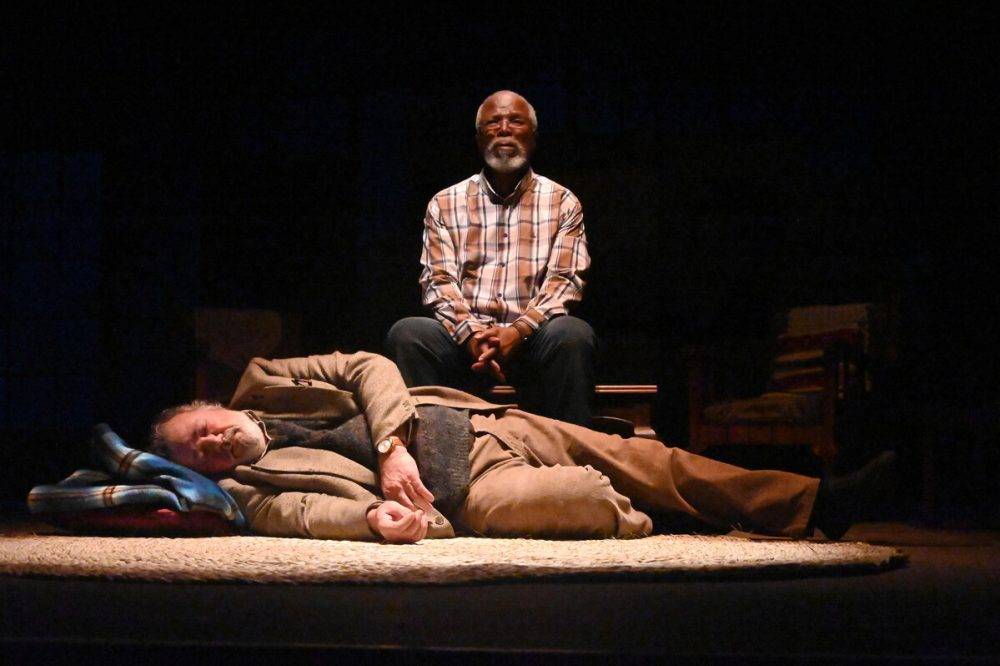

Play right: Dr John Kani and Michael Richard in the première of Kunene and the King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre in Joburg in 2022. (Photo by Oupa Bopape/Gallo Images via Getty Images)

Play right: Dr John Kani and Michael Richard in the première of Kunene and the King at The Mandela Joburg Theatre in Joburg in 2022. (Photo by Oupa Bopape/Gallo Images via Getty Images)

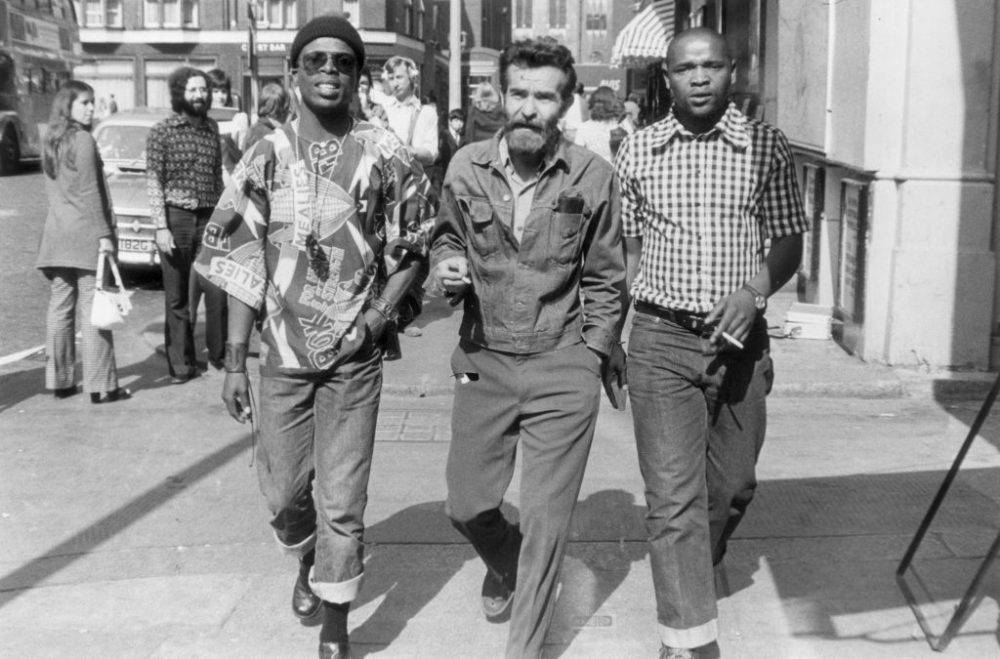

The first time he landed in Britain was in 1973 to perform the powerful protest play Sizwe Banzi is Dead. Exactly 50 years later he is getting this OBE medal in recognition of that work — and so much more.

The high commissioner tells me in an email after our meeting that it “recognises Kani’s outstanding achievements and service to drama”.

“The UK honours system allows individuals to be nominated to reward noteworthy contributions to the arts, sciences, charitable work and public service.”

Kani continues: “No, I never questioned it, but it did cross my mind that some radical here who knows me to be part of a struggle for the humanity and identity of being African is going to say, ‘Isn’t there a contradiction, sir?’

“‘At the same time, you’re still fighting and keep talking about the problems that this country faces dating back to colonialism, to the apartheid era, to the 30 years, today?

“‘And all that is an impact on what our people are and what our economy and our country is?’”

Kani takes another sip of his coffee and resumes. “And yet I then say, ‘John Kani, OBE.’”

He is, of course, a master storyteller. Some of his delicious stories deserve to be on stage. Just a tale about the absurd apartheid bureaucracy is told with colour, perfect timing and humour — as if you were there, looking on. And, as a bonus, it is presented in that beautifully mellifluous Kani voice.

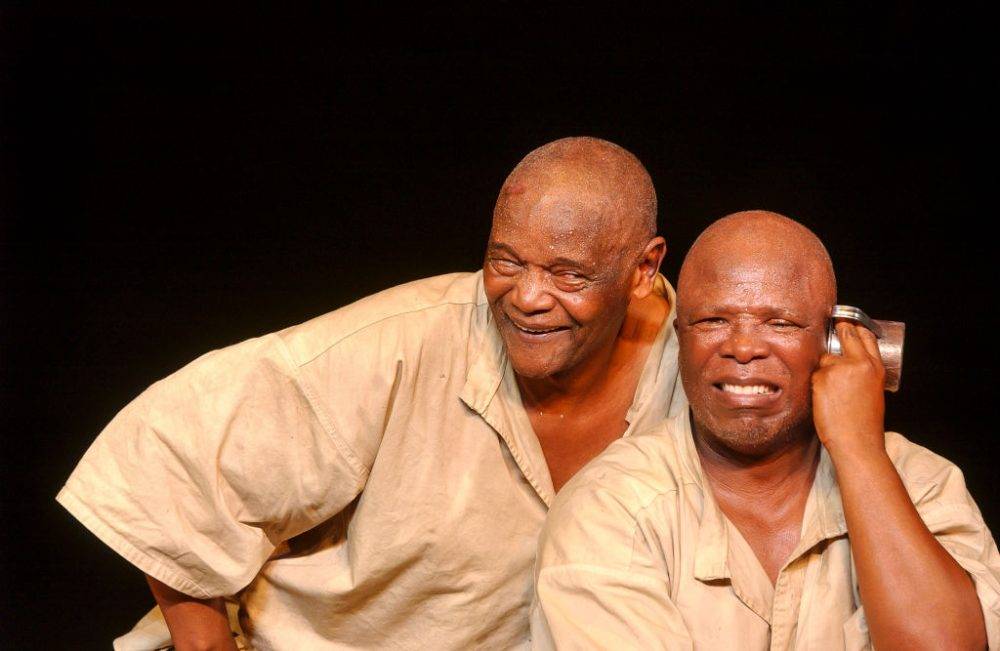

John Kani and Winston Ntshona in The Island. (Photo by Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images)

John Kani and Winston Ntshona in The Island. (Photo by Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images)

He takes me back to Cape Town’s Space Theatre in 1972, when he and his late comrade-in-charms, Winston Ntshona, first performed Sizwe Banzi is Dead, which they co-wrote with Athol Fugard.

In the audience was Nicholas Wright, head of the theatre upstairs at the Royal Court Theatre. He sent Fugard an invitation to do the play in London.

“We sat down and our first response was ‘no’. Winston and I said, ‘What’s the point?’

“‘What are we going to do with the English? This play speaks to the advancement of our cause here in South Africa.

“‘We’re going to go to do it in England. It’s going to be an evening’s entertainment. And then we come home and then what? We have to continue this struggle.’”

But after further discussion they thought perhaps there was another audience. There was the constituency of exiled South Africans.

So the three shit-stirrers applied for passports. Four weeks later, Fugard gets his. Ntshona’s takes eight weeks.

“I don’t get the passport,” Kani says with a side smile. “Because, at that stage, I had been detained a couple of times for being a member of the underground structures and cultural structures. At that stage, my uncle was already on Robben Island.”

But it then got to the point where they had to decide whether they were going or not.

“Then I had this brilliant idea. I did a nice call to [the formidable left-wing MP] Helen Suzman: ‘Helen, can you help?’”

Out of the blue Kani got a call. He must report to the Civitas building in Pretoria the following day, even though he lived in Port Elizabeth. He scrambled to get a plane ticket.

His friend, theatre impresario Mannie Manim, picked him up at the airport “in his old sort of Kombi thing, that old Volkswagen Kombi”.

“We drive to Pretoria. We go to this building. I’ve never been to Pretoria. I’ve never seen so many white people in uniform.

“We go to the seventh floor. We come in and the ‘council of God’ was sitting there. All white.”

Kani gets a dressing-down. “Who the hell do I think I am to get Mrs Helen Suzman involved?!”

After an interrogation, Kani finally gets given his odd-looking passport. Unlike the normal green South African one, it is brown.

When they are outside in the street, Kani and Manim finally open it.

“First page, nationality ‘onbepaald/undetermined’…”

Kani guffaws at the memory of his first passport. “I still have the copy at home: ‘onbepaald-stroke-undetermined’!”

That travel document had a line that said, “The South African government bears no responsibility for the bearer of this document.”

More laughter.

But it served Kani and his fellow opstokers (agitators) well. Sizwe Banzi’s British première won a London Theatre Critics Award for the Best Play of 1974.

It ran for 159 performances in New York. In 1975, with The Island, it won Kani and Ntshona a prestigious Tony Award, which recognises excellence in live Broadway theatre.

Actor John Kani, director Athol Fugard and actor Winston Ntshona, co-writers of Sizwe Banzi is Dead, at the Royal Court Theatre, London, where they performed the play in 1973. (Photo by James Jackson/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

Actor John Kani, director Athol Fugard and actor Winston Ntshona, co-writers of Sizwe Banzi is Dead, at the Royal Court Theatre, London, where they performed the play in 1973. (Photo by James Jackson/Evening Standard/Getty Images)

And on the night of our interview Kani would be getting his OBE officially awarded in the same Pretoria.

I ask him: Who would you have liked to see you being honoured with this OBE who’s no longer around?

He pauses several seconds and replies quietly.

“It’s my father.”

They did not always have the best of relationships. In 1995, Kani wrote a thesis about his theatre practice — his work in protest theatre and his vision of theatre in a democratic South Africa — which earned him a PhD at what was then the University of Natal-Westville.

Afterwards, Kani went to his hometown of Port Elizabeth to visit his family. His mom, who had a great sense of humour, said, “By the way, I hear from the neighbours of the doctor now.

“Which hospital can I go see you?”

That raucous Kani laughter.

“And my dad said, ‘What does it mean? Nothing?’

“I said, ‘No, it just means art.’”

Kani has a gentle smile on his face as he returns to my question.

“He would have been the person I would have been with tonight … It’s my dad.”

Whenever Kani travelled, he always bought his old man a litre bottle of Red Heart rum, “because we’re not selling litres in South Africa. And it would be duty-free.

“And whenever you asked him, ‘What’s your son doing?’ he said,

‘I don’t know. He’s always away.’

“‘Maybe one day he’ll get a job.’

“But my mum says, ‘But he’s happy.’ And they would argue about it.”

In 1995, not long after his PhD, Kani came home from abroad. His dad and three of his friends are sitting on the veranda of their New Brighton home.

“He said, ‘Oh, you’re back?’

“I said, ‘Yeah,’ and gave him the Red Heart rum.

“He looked at me, turned to his friends with the rum and joked, ‘This is not for illiterates. This is for only class people.’

“And then he said: ‘Guys, this is my son. John Kani is an actor.’”

I look at Kani through his glasses but he is looking elsewhere.

“He died three months later. He gave me that gift of finding the words in his mouth, form them, and accept that I am an actor.”

It has become a justifiable cliché that South Africans box above their weight in the international arena — because many do. For all his global achievements, Kani must be a multi-gold medallist.

In addition to his acclaim on theatre stages across the world, he is also known for playing film roles — there’s T’Chaka in the Marvel films Captain America: Civil War (2016) and Black Panther (2018). He is also Rafiki in The Lion King and Colonel Ulenga in the two Murder Mystery Netflix movies.

I ask Kani if he has been getting the recognition he deserves here in South Africa.

“In 2000, during Thabo Mbeki’s rule, I received the national honour of the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver, for my contribution to the liberation of South Africa, and ‘through his work for the creation of a democracy’ — that’s what the citation reads,” Kani tells me.

“Yes, that, for me, began the understanding that my government, my people, recognise me.”

One evening, as Kani was walking out of the theatre after a performance of his 2014 play Missing, a young girl approached him and said her mom wanted to say hi.

“And she says, ‘You know, I’ve seen all your plays. Congratulations, John.’

“But then I want to shake her hand. She does this.”

Kani points his hand slightly away from me, acting the woman.

Then he realised.

“And I’m standing here … She’s blind. She is blind. She just said to me, ‘I have seen all your plays.’

“I had a tear in my eye and this girl says, ‘I brought mum to every play, ever since Master Harold, everything.’

“And she says, ‘I’ve seen all your plays.’ And she shakes my hand there.

“What more would I ask? Nothing.”

South Africa has a new minister of sports, arts and culture in Gayton McKenzie, and with the proverbial jury still out, I ask Kani what advice he would give the new guy.

He is diplomatic and, at the same time, optimistic.

“The president has made a choice. I believe, to have reached that level in his development as a service politician, he must have conversations.

“And, as any other minister would do in the handover, to understand the beast in his totality. And I believe with the willingness and the enthusiasm, he could be directed and redirected towards a journey that benefits this constituency.”

At 81, Kani is far from retirement. He is completing work on The Lion King, officially revoicing Rafiki. He is also in negotiations with a Broadway producer who is taking the play Kunene and the King to America.

I ask Kani what his greatest extravagance is.

“Wow, jazz records. I’ve still got a turntable, and my money goes from Miles Davis to Ornette Coleman to Count Basie to Duke Ellington to Glenn Miller, to all the big orchestras.

“I have to pay forever extra weight at the airport — and it’s nothing but these records.”

But then he remembers something else. “My other extravagance now at my age is spoiling the grandchildren. I’ve got 10 grandchildren and that infuriates their parents because they’re unable to do this.

“Everybody says, ‘We’re going to Granddad’s home, because Granddad buys us this and Granddad buys us that.

“‘And, at Granddad, we don’t sleep early. We can do anything.’

“And I say to my children, ‘I did spoil you too, so give me a chance to play with these things that call me Granddad.’”

It is time to be off — so my last question: Who should play John Kani in your biopic?

Kani doesn’t hesitate: “Now, I’m going to say something very selfish. My son, Atandwa.”

In 1987, Kani played Othello in an acclaimed production. Atandwa recently played the same role, also to great acclaim.

“It was like déjà vu — I’ve been here before, looking at him, I thought, ‘My God, he does look like me.’

“If I had doubts anywhere, anywhere in my life, he is my son.

“So, if there was going to be a biopic about my life, and he was available, I’d ask the director to approach him.”

Honoured for his legacy

British High Commissioner to South Africa Antony Phillipson explains why John Kani was appointed to the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

Kani receives his OBE in Pretoria.

Kani receives his OBE in Pretoria.

What is the significance of honouring someone in theatre?

It is a testament to the UK and SA’s mutual love of arts and culture and to their power to unite, inspire and to transform lives, perceptions and communities. It further underlines the importance of creativity and its role in innovative and dynamic societies.

What makes John Kani special?

He represents South Africa in an iconic way through his immense contribution to sharing important works locally and globally. His OBE, alongside his many South African and global awards and commendations, speaks of the great impact of his legacy. The fact that he clearly has no intent to slow down speaks to his ongoing passion and commitment to dealing with injustice in all its forms.

(Photo by MARCO LONGARI / AFP)