Vision of the future in the east: HDF predicts Renewstable Mpumalanga’s green energy can mitigate up to half of the Eskom load-shedding stages. Photo courtesy HDF

Mpumalanga is the home of Africa’s largest green hydrogen power projects, according to a French company planning to invest $3-billion in green energy in Standerton, a commercial and agricultural town in the east of the province.

Hydrogène De France’s ambitious plans include installing 1 500 megawatts (MW) of solar PV combined with 3 500 megawatt-hours (MWh) of hydrogen storage. The projects will inject 1.9 terrawatt hours of stable electricity into the grid 24/7 and will peak at about 500MW, says Nicolas Lecomte, company director for Southern and East Africa.

“Hydrogène De France [HDF] envisions that this 500MW of green energy can mitigate up to half of the [Eskom] load-shedding stages, marking a pivotal transition toward cleaner and more reliable electricity for South Africa. This project will provide electricity to an equivalent of 1.4 million inhabitants all day and all night, all year round,” Lecomte said.

“When it comes to hydrogen power plants, the HDF Renewstable Mpumalanga project is the largest. The word ‘power’ is essential. Hydrogen infrastructure projects can be of a very different nature, for different applications,” he said.

World Bank experts say South Africa has 20 projects linked to green hydrogen across the country. Most of these projects are in the Western and Eastern Cape, with three being developed in Mpumalanga: the Sasol Hyshift project in Secunda, the Camden Green Hydrogen and Ammonia facility in Ermel, and the HDF Renewstable Mpumalanga development in Standerton — the first HDF project in South Africa.

Renewstable Mpumalanga is not one of the nine priority projects registered in the Government Gazette and identified as strategic infrastructure priority projects for the government in partnership with business and other sectors. Lecomte said HDF aims to conclude the registration and permitting processes for the first Renewstable units in the first quarter of 2025.

Land lease

The project is an outcome of Eskom’s land lease agreements with independent power producers for the commercial use of land parcels near two of its coal-fired power stations in the province, Tutuka and Majuba.

In April 2022, Eskom initiated a request for proposals, launching a selection process to lease 6,184 hectares of land for 25 to 30 years. HDF Energy secured 1 782ha to develop green baseload power plants.

HDF is a French independent power producer specialising in hydrogen power. It has expanded its operations into the Southern African market and is developing several green hydrogen (GH2) projects in various other parts of the world and Africa, including Namibia, Zimbabwe and Kenya.

Lecomte said HDF’s expansion into the Southern African market with the launch of its Renewstable Mpumalanga project was motivated by several factors, including the abundant natural resources that make the region conducive to renewable energy production, in a national and regional context of power-generation deficit.

“Another factor is that the regulatory environment in South Africa and neighbouring countries is conducive to renewable energy investments. Mpumalanga, being the focal point of the Just Energy Transition, is also a renewable energy resource-abundant province,” he said.

The Renewstable Mpumalanga project will play a role in the energy transition by supplying two major nodes of the electricity grid close to the two local coal-fired power stations, said Lecomte. It will also sell the power to its own customers, which could include commercial and industrial clients.

“What sets Renewstable apart from other renewables, such as wind and solar, is its ability to provide round-the-clock, adjustable, grid-stabilising power. From a technology perspective, the introduction of this new type of power plant is a revolution. It addresses a key challenge associated with renewable energy sources — their intermittency,” he said.

Nicolas Lecomte: 'What sets Renewstable apart from other renewables is its ability to provide round-the-clock, adjustable, grid-stabilising power.' Photo supplied

Nicolas Lecomte: 'What sets Renewstable apart from other renewables is its ability to provide round-the-clock, adjustable, grid-stabilising power.' Photo supplied

Eskom relationship

Speaking about Eskom’s relationship with the developer, the utility’s media desk said, “This is a specific programme where Eskom will lease land over a long period to renewable developers for the establishment of renewable generation. The developer is responsible for all development, approval, construction, etc.”

Eskom anticipates capacity from the Renewstable Mpumalanga project to come online from the end of 2026. “The developer will sell the energy to their own customers, with Eskom managing the wheeling of the energy to their customers or own offtake points.”

The utility explained that the intention of its relationship with independent power producers is to unlock opportunities for the private sector to expedite new-generation capacity in managing the constrained electricity system.

“Eskom supports the implementation of cost-effective, proven commercial technologies and is also researching green hydrogen with the possibility of a small demonstration plant,” the media desk said.

When asked to elaborate on specific requirements or conditions outlined in the land lease agreement regarding the use of the land for renewable energy development and associated infrastructure, the desk responded: “Specific contractual matters are confidential."

“However, the intent from Eskom is to allow as much freedom as possible to the developer to generate new capacity. Eskom does not procure the energy and the developer is free to produce products that they require or can sell commercially. The source of generation must be renewable in nature and all legislation needs to be adhered to,” Eskom said.

While these kinds of agreements might come with financial implications, Eskom would only say that there would be implications associated with the land lease agreement. However, the media desk would not elaborate further, saying this was confidential contractual information.

Avena Jacklin: 'Green hydrogen presents a technology change that is largely untested and driven by market share, rather than meeting local needs.' Photo supplied

Avena Jacklin: 'Green hydrogen presents a technology change that is largely untested and driven by market share, rather than meeting local needs.' Photo supplied

Civil society concerns

In South Africa, an accelerated push for GH2 facilities has been facilitated through the Green Hydrogen Commercialisation Strategy, given the green light by the cabinet in October 2023. Natural Justice and other civil society organisations have recorded the effect of GH2 projects on two sites: Boegoebaai in the Northern Cape and Ermelo in Mpumalanga.

According to a recent Natural Justice report, communities in Boegoebaai and Ermelo said they had not been provided with information on what GH2 is, how it works, who it will benefit and how it will impact local communities. When there has been public consultation, the communities said, it had been insufficient. Natural Justice believes this violates the Constitution’s guarantees of administrative justice and public access to information.

Avena Jacklin, operations director of environmental justice organisation GroundWork, told said: “While GH2 agreements are a response to pressures for change, they are largely dependent on local natural resources (mainly land and water) and foreign technical human capital, for the benefit of the north — rather than based on an endogenous transition. Justice and open and participatory democracy are compromised in this way.”

According to Jacklin, mega projects promise more than can be delivered and tend to over-extend their allocated budget and time. They inevitably result in soil and water pollution, affecting both surface and groundwater and the loss of agricultural land, as well as the displacement and relocation of communities and loss of ecosystem services, she said.

“Land users comprising mainly the informal economy are not consulted or included in the inception phase or decision-making processes,” she said.

Jacklin maintained that even though GH2 projects may address the need to decarbonise heavy industrial manufacturing and chemical processes, “the capitalistic approach of mega projects has intensified the commodification of our natural environment with agreements that bind us further into the mineral-energy complex model that our current crisis of inequality and poverty has arisen from”.

“Green hydrogen in this format presents a technology change that is largely untested and driven by market share, rather than meeting local needs, and has already proven to be exclusionary and polluting. With volatile markets and oversupply over the next decade or two, it may be headed for a market bust, leaving a largely changed landscape and deepening our poverty crisis,” she added.

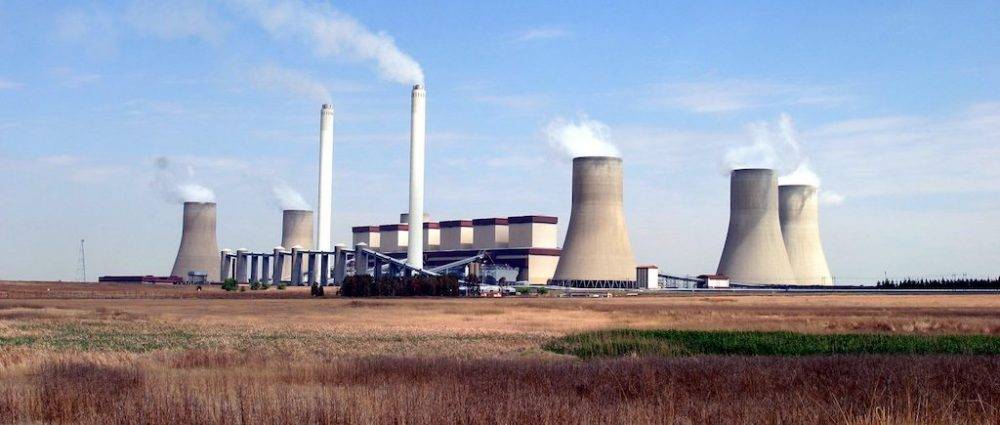

Land lease: Renewstable Mpumalanga is situated on 1,782ha near two of the province's coal-fired power stations, Tutuka (above) and Majuba. Photo courtesy Eskom

Land lease: Renewstable Mpumalanga is situated on 1,782ha near two of the province's coal-fired power stations, Tutuka (above) and Majuba. Photo courtesy Eskom

Land use rights

Lubabalo Majenge is the head of communications at Lekwa municipality, where the Renewstable Mpumalanga project is being developed. He explained the role of the municipality when these projects are taking place in their area: “It is mainly to process the land use rights application submitted to the municipality in line with the requirements of the Spatial Planning and Land Use Act, read together with the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management by-law of Lekwa Local Municipality.”

According to the HDF proposal submitted to the municipality, jobs will be created during construction and post-construction, he said.

Majenge emphasised the importance of community involvement in the project and shared what he believes will work: “We insist on the establishment of a project steering committee that consists of representatives from various stakeholders to ensure that the local community is well represented and informed about the project.”

Some challenges might arise during its development, such as untraceable land claimants on some of the farm portions, unreasonable or unrealistic expectations of timelines, undue pressure on municipal officials and the fear that the introduction of renewable energy will lead to the closure of the Tutuka power station, resulting in job losses, Majenge said.

“However, the municipality is already addressing these challenges through engagements with Eskom.”

Blessing Manale, head of communication at the Presidential Climate Commission, said it was still too early to predict the future of GH2 in South Africa.

“As we decarbonise, certain challenges can only be effectively addressed using green hydrogen (hydrogen produced using renewable energy). However, it is too early to say what will happen with hydrogen. It is an important technology but its affordability and implementation timing will depend on international research efforts and local policy decisions,” he said.

According to Manale, while GH2 is an expensive, but promising, opportunity, with most technological barriers overcome, its use in power plants is unlikely in the near future.

“We will probably not use green hydrogen in power plants until later in our journey to net-zero” when the amount of harmful greenhouse gas emissions being produced balances with the amount being removed from the atmosphere, he said.

“Burning hydrogen in power plants would be more expensive than other options and would require significant additional renewable energy to produce the green hydrogen.”

Thabo Molelekwa is an associate journalist of Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism and a graduate of its #PowerTracker professional support and training programme. This investigation was supported by the African Climate Foundation’s New Economy Hub.

You can track the development of energy projects across Mpumalanga on the Oxpeckers #PowerTracker tool.