Photo: Salam Habash / Unsplash

Wheeling is a method of sharing electricity that offers a solution to some of the country’s grid constraints, and an opportunity for the uptake of renewable energy in Mpumalanga as coal-fired power generation declines.

Wheeling of electricity generated by third parties has been approved by state utility Eskom since 2008. It addresses the geographical limitations of Mpumalanga, which a #PowerTracker data investigation in early 2023 showed, has missed out on renewable energy despite the planned decommissioning of coal power stations based in the province.

New research released in July by the South African Local Government Association (Salga) indicates that the wheeling market is still in early stages and only four municipalities have some sort of operational wheeling system in place. None is based in Mpumalanga.

“Mpumalanga has lots of grid capacity available to connect generators who can wheel their power to large energy users in other provinces of South Africa,” said Josh Dippenaar, project manager at Sustainable Energy Africa, one of Salga’s partners.

“Wheeling represents an opportunity to build power plants in areas where the local economic benefits of renewable energy are highest, and they can sell their electricity via the grid — that is, ‘wheel the power’ — to urban areas where the electricity can be consumed,” he said.

Eskom: ‘Wheeling helps customers achieve renewable energy targets and facilitates private participation in the electricity supply industry to add additional generation capacity’

Eskom: ‘Wheeling helps customers achieve renewable energy targets and facilitates private participation in the electricity supply industry to add additional generation capacity’

Wheeling process

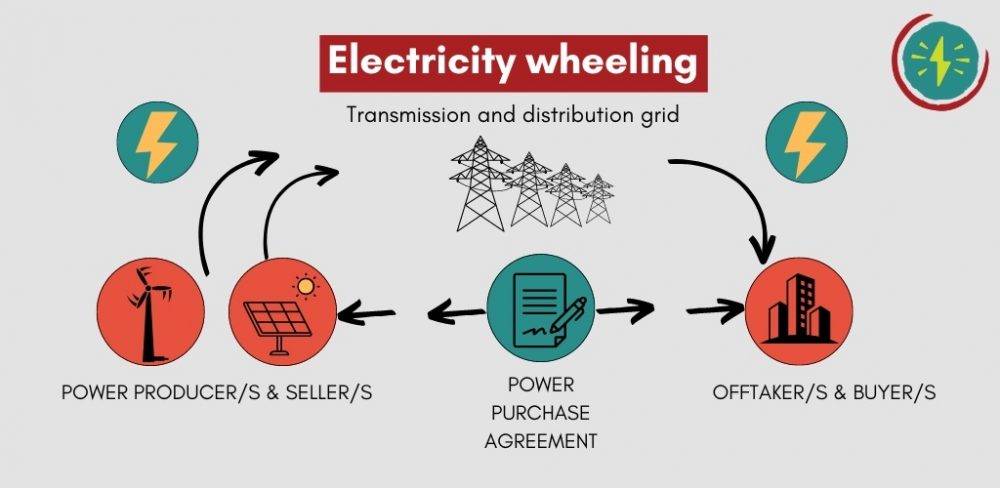

Wheeling of renewable energy from a plant in a part of the country where there are grid constraints to an end-user located in another area takes place through an existing distribution or transmission network.

“This process usually involves electricity that is generated in more remote areas being transported to wherever the customer or offtaker is located,” said Wikus Kruger, director of the Power Futures Lab at the University of Cape Town’s Graduate School of Business. “It’s not like you have solar panels on the roof of the factory or even next to the factory. They will be quite far away.”

Wheeling is a way of getting private investment into the sector, he added. “Companies will pay a fixed fee to Eskom for wheeling the power; it’s a fee that’s supposed to cover the cost of running and maintaining the grid.” The actual cost of power being generated gets paid to the renewable energy plant by the offtaker company.

According to Eskom, wheeling is the delivery of energy over the grid. Customers enter into third-party bilateral transactions where they buy power from a private generator. This energy is delivered by Eskom over the grid.

“More and more customers are looking into entering into private power purchase agreements [PPAs] … for reasons such as [meeting] renewable energy targets and creating additional generation capacity to alleviate load-shedding,” said Eskom’s media desk in response to questions from Oxpeckers.

“Wheeling helps customers achieve renewable energy targets and facilitates private participation in the electricity supply industry to add additional generation capacity.”

Kruger said a problem with wheeling is that it’s only possible within the municipal space, and it’s challenging because the rules and regulations need to be set up by the municipalities themselves. He added that a potential solution being worked on is called virtual wheeling.

Virtual wheeling aims to reduce the barriers of the traditional wheeling method, which only allows for bilateral trade agreements between generators and buyers. Virtual wheeling allows one or more generators to transact with multiple offtakers, giving the customer the option of significantly reducing the term of a PPA as compared to traditional one-to-one wheeling arrangements, according to energy analysts Linsey Dyer and Chris Yelland.

On August 30, telecommunications giant Vodacom and Eskom announced an historic virtual wheeling agreement, enabling Vodacom to secure renewable energy from independent power producers on the same terms and conditions that underpin its agreement with Eskom.

Vodacom South Africa chief executive Sitho Mdlalose reportedly said the initial phase of the deal would move about 30% of Vodacom South Africa’s power demand onto renewable sources. “Think of it like purchasing renewable energy certificates,” he said. “Most importantly, it also has the added benefit of positively impacting the supply deficit currently being experienced and nurturing the growth of renewable energy production in South Africa.”

The Noupoort wind farm in the Northern Cape: Most of the national grid capacity has been taken up in the three Cape provinces. Photo: Mainstream Renewables

The Noupoort wind farm in the Northern Cape: Most of the national grid capacity has been taken up in the three Cape provinces. Photo: Mainstream Renewables

Examples down south

The Nelson Mandela Bay metro municipality in the Eastern Cape has been a frontrunner in the wheeling space, according to the July Salga report. With more than 10 years’ experience, roughly 2.5% of the energy flowing in the metro is wheeled energy.

In 2012, the council passed a resolution to source 10% of the total electricity consumption in the municipality from renewable energy sources, with an emphasis on local projects. According to the Municipal Wheeling Agreement for green power development, the municipality would wheel such power from private producers to willing buyers.

Once approval from the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) was obtained, the first, non-exclusive 20-year wheeling agreement was signed between the municipality and Amatola Green Power. To date 5 000 megawatt hours are wheeled annually from private renewable energy developers such as the Electrawinds wind farm at Coega to willing buyers through the municipal network.

The City of Cape Town and George municipality are in the early stages of wheeling pilots, with the latter bringing in small wheeling volumes envisioned to grow as new generators connect to the wheel. The Cape Town wheeling service is expected to be fully operational by the end of 2023.

According to the Salga report, the City of Ekurhuleni metro in Gauteng has been receiving a growing number of requests to wheel and has responded by developing a wheeling policy that has been approved by the city’s council. Some KwaZulu-Natal municipalities — eThekwini, uMhlathuze and Msunduzi — and some Western Cape municipalities are in talks to make a start towards wheeling.

Many mines and commercial clients are already invested in wheeling because it’s ‘cost imperative’. Photo: Seriti Resources

Many mines and commercial clients are already invested in wheeling because it’s ‘cost imperative’. Photo: Seriti Resources

Grid availability

Gaylor Montmasson-Clair, a senior economist at Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies, said to date Mpumalanga has not been a major destination for renewables projects because other provinces such as the Northern, Eastern and Western Cape provinces have offered better returns.

But there are grid availability challenges in those provinces. “Most of the capacity seems to have been taken up in the grid in all three Cape provinces, which is also where a lot of the really good resources are,” said Montmasson-Clair.

“So now developers both for the public and private sectors are looking at other locations. The two provinces that have the most grid available are Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal, each with roughly 6 000 megawatts of grid available.”

This means they are ripe for wheeling, but the process is complex legally and in terms of accounting and payments, said Peter Attard Montalto, managing director and global lead on the Just Energy Transition at financial services consultancy Krutham, formerly known as Intellidex.

“The problem in South Africa is that there is no standardised structure for how it works — this is what the National Energy Crisis Committee is working on quite successfully at the moment, though the answer will take some time yet to socialise and deploy.

“Currently, wheeling does happen, but it’s very ad hoc and you have to negotiate numerous contracts for every step of the path of the grid, which is unworkable at scale. This is what the committee work hopes to solve.”

According to Montalto, wheeling will open Mpumalanga to a corporate market to buy, sell and trade power with offtakers all over the country, so it’s not reliant on the size of Mpumalanga’s economy.

The unbundling of Eskom to create a new National Transmission Company “is positive if done correctly because it promises to offer a higher credit quality that can borrow more to invest at scale in transmission and remove this and other blockages”, he said.

Duvha coal-fired power station in Mpumalanga: the province has about 6,000MW of grid available. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Duvha coal-fired power station in Mpumalanga: the province has about 6,000MW of grid available. Photo: Ashraf Hendricks

Fast-track wheeling

Dippenaar highlighted a lack of sufficient human resources as one of the causes of the delays in fast-tracking wheeling across South African municipalities. “Larger municipalities have bigger staff contingencies and more capacity to focus on new areas of work such as wheeling,” he said.

Kruger said another obstacle was the indebtedness of many municipalities to Eskom, or just poor municipal financial management. “It’s often difficult to get investments for these projects that are wheeling within municipalities because the financial instability in the municipality is posed as a risk to the project,” he said.

Many mines and commercial clients are already invested in wheeling, he added: “There are a lot of wheeling transactions being developed. It’s cost imperative, because the energy renewable plants generate is generally cheaper than what Eskom is providing and what Eskom is likely to be costing in the near future. So they’re doing this to save costs.”

These transactions should pave the way for development of the wheeling regulations and the kind of contracting that should take place for new projects, he said.

“We are seeing a lot of movement in areas where there are less grid constraints. Mpumalanga is one area, KwaZulu-Natal is another. There’s a whole kind of corridor of areas with great capacity available where wheeling projects are being developed,” Kruger said.

Andiswa Matikinca and Thabo Molelekwa are associate journalists of Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This investigation was supported by the African Climate Foundation’s New Economy Campaigns Hub