A general view of a classroom at Kuriga school in Kuririga on March 8, 2024, where more than 250 pupils were kidnapped by gunmen. (Photo by HAIDAR UMAR/AFP via Getty Images)

It happened at around 8.30am on Thursday 7 March. Pupils at the Local Education Authority primary school in Kuriga, in Nigeria’s northern Kaduna State, were gathered on the assembly ground.

There were more students there than usual: the nearby secondary school had been closed due to security concerns, so all the older children were being taught on these premises. They were waiting to begin what should have been an ordinary school day.

Suddenly, armed men on motorcycles appeared, racing towards them. Teachers were powerless to prevent the attack. The kidnappers bundled some children onto the back of their bikes, while others were forced to walk at gunpoint. They shot at children who tried to flee.

By the time the chaos had subsided, and the headmaster was able to do a headcount, more than 300 children and several teachers had been abducted. It is believed that every family in the small, tight-knit community has at least one child among the abductees.

A few were able to escape as they were marched into the dense forests that surround Kuriga. One of the escapees, Mustapha Abubakar, later described how a long line of children was made to trek over great distances, and told to crawl when they got tired. The only time they were able to drink any water was when they crossed a river.

At one point, a plane hovered overhead, and the kidnappers ordered everyone to remove their clothes and lie down on the ground to avoid detection.

Abubakar seized the opportunity. “The bandits were exhausted, had no food. We saw them eating leaves and wild fruits but they gave us nothing to eat,” Abubakar told BBC Hausa. “While we were moving, I noticed a shrub that was brown in colour, like my trousers. I hid inside and crawled like a snake. I was there until it was completely silent before I came out and headed to the bush.”

It took Abubakar many hours of walking alone through the forest before he reached a village where he received help. He was one of the lucky few to escape. No one knows where the rest of the children are, or even who took them.

The government has promised to do everything it can to bring the children back unharmed.

Soldiers are combing the forests, but so far the search has been fruitless.

The kidnappers have demanded a ransom of one billion naira ($622,000), to be delivered by 27 March – or else all the students will be killed.

Omar Zaghloul/Anadolu via Getty Images

Omar Zaghloul/Anadolu via Getty Images

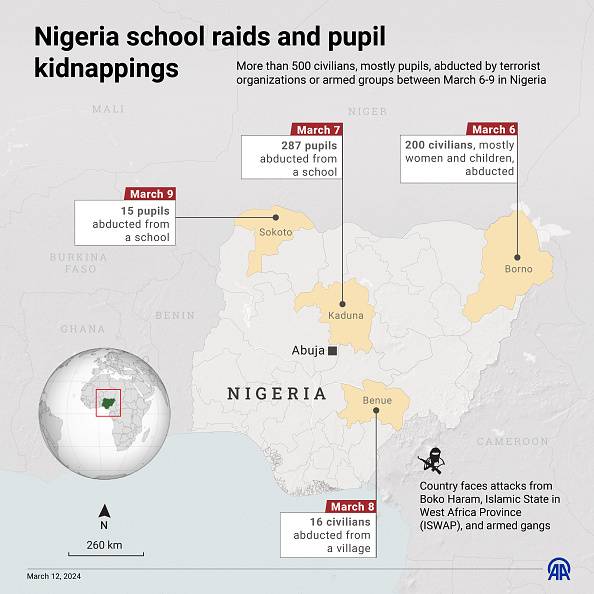

Nigeria has a mass kidnapping problem, and this has been an especially horrific month.

On 6 March, 200 civilians – mostly women and children – were taken from a camp for internally displaced people in Borno State.

On 7 March, 287 children were taken from Kuriga.

On 8 March, 16 civilians were taken from a village in Benue.

On 9 March, another school was targeted – this time 15 schoolchildren were taken from their rooms late at night, along with one woman in Sokoto State.

And on Tuesday last week, at least 61 people were taken from their homes in a village in Kaduna State’s Kajuru district.

The perpetrators of the kidnappings – not thought to be connected to each other – are usually described as “bandits”, a catch-all term in Nigeria that encompasses everything from armed criminal groups to terrorist organisations. Usually a ransom is demanded. That’s why schoolchildren are a popular target: parents and schools can’t afford large sums, but the headlines generated may force the government to pay up.

The template for this is, of course, the most notorious mass kidnapping of them all: the kidnapping of 276 young girls from Government Girls Secondary School in Chibok, Borno State, in April 2014 by the Islamist militant group Boko Haram.

Some girls escaped in the immediate aftermath, but at least 219 were held in the Sambisa Forest, and some were forced into sex with Boko Haram fighters.

It was only in 2017 that the Nigerian government agreed to pay a ransom. The amount has never been confirmed, but media reports suggest it was in the region of $3-million in exchange for the release of 82 girls.

A group of girls previously kidnapped from their boarding school in northern Nigeria arrive on March 2, 2021 at the Government House in Gusau, Zamfara State upon their release. (Photo by Olukayode Jaiyeola/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

A group of girls previously kidnapped from their boarding school in northern Nigeria arrive on March 2, 2021 at the Government House in Gusau, Zamfara State upon their release. (Photo by Olukayode Jaiyeola/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

It is believed that more than a hundred are still being held captive.

The fate of the Chibok girls, and the government’s inability to protect them, sparked a worldwide solidarity movement known as #BringBackOurGirls, and heaped enormous pressure on then-president Goodluck Jonathan’s administration, which played a significant role in his electoral defeat in 2015.

For current President Bola Tinubu, the stakes may be just as high.

He promised to tackle insecurity, and the country will be watching closely to see how he deals with this crisis. So far, he has emphasised the role of the security forces in locating kidnappers and releasing victims.

One thing he won’t be doing – not officially, anyway – is paying any ransoms. In 2022, in an effort to deter further kidnappings, the government criminalised the payment of ransoms, with a minimum jail term of 15 years for anyone found guilty of doing so.

“The government is not paying anybody any dime and the government is optimistic that these children and other people … will be brought back to their families in safety,” he said on Thursday.

Those families, who have called on the government to do more, do not appear to share the president’s optimism.

This article first appeared in The Continent, the pan-African weekly newspaper produced in partnership with the Mail & Guardian. It is designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Download your free copy at thecontinent.org