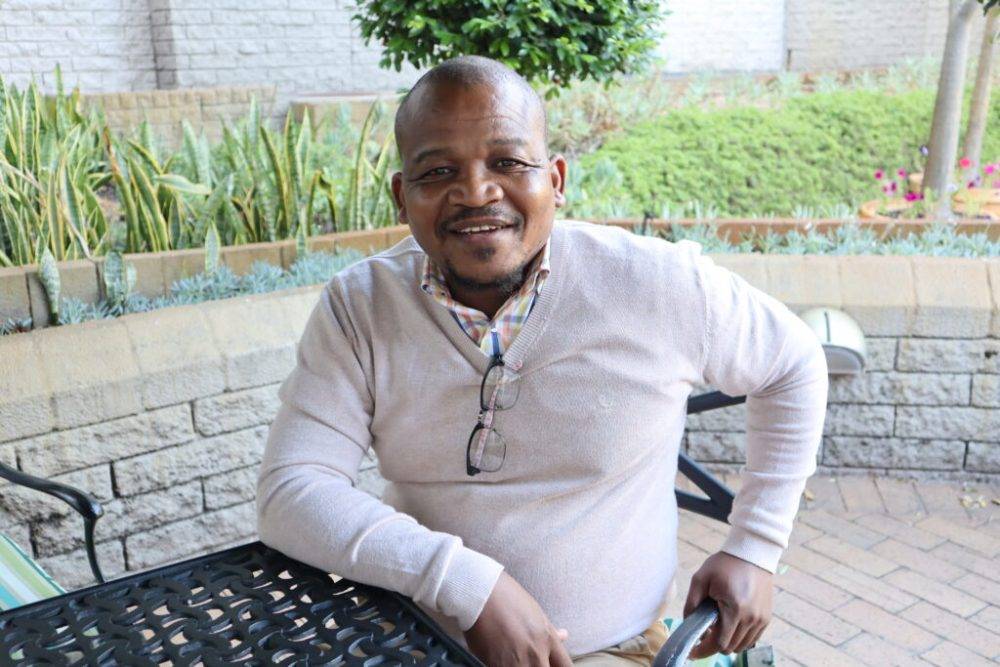

ROAD TO SUCCESS: Many of the early graduates of the SA–Cuba medical training programme now hold senior leadership positions in SA’s health sector.

There is an obscure significance to Mzulungile Nodikida’s appointment as CEO of the South African Medical Association (Sama) in January this year and it derives from Nodikida being a product of the South African government’s Cuban Medical Training Programme, sometimes called the Nelson Mandela-Fidel Castro collaboration.

Since its establishment in 1996, the programme has been knocked for being impractical, too expensive and for producing inferior doctors. In a 2013 South African Medical Journal article, Sama’s then vice chairperson, Mark Sonderup, is quoted as saying, “[E]verybody agrees we need more doctors, but is this the best we can do?”

Nodikida now leads Sama and he isn’t the only Cuba graduate who has accessed power and influence in South Africa’s healthcare sector.

“There are a few of us, mostly early graduates, which isn’t surprising because we’ve had time to accumulate experience. In a few years our juniors will eclipse us,” says Nodikida, although he concedes that things were a bit different in those earlier years, when the rough edges of the programme were still being smoothed.

“Perhaps those who made it through were hardened and enriched by that, I don’t know,” he muses.

Sanele Madela, a former classmate of Nodikida who is the the health department’s attaché to South Africa’s Havana mission, says that any special quality the earlier cohorts possessed “is probably related to fewer spaces having been allocated in those days, so they were really sending the cream of the crop”.

He searches his memory for the numbers to illustrate his point.

“There were, I think, only 11 students from KwaZulu-Natal in my 2002 group, whereas in later years the province sent 100 to 200 students.”

Madela says he, Nodikida and some others in their cohort used jokingly to each other CEOs.

“We still laugh about that because today we are, or have been, CEOs [of medical facilities and organisations].”

A survey of Cuba- and South Africa-trained graduates published in 2019 found that those from the Cuba programme reported “stronger motivation for creativity and initiative in their career, to work in rural areas, to improve health of the country and to become a community leader”.

This would have made gratifying reading for the programme’s architects, who aimed to address a dearth of doctors in South Africa’s rural areas, particularly, by sourcing students from those areas in the hope that they would be more likely to want to return to work in their own communities.

Context and the underdog factor

“I’m not going to sit here and pretend that it wasn’t a political programme,” says Madela, who is today responsible for monitoring the programme that trained him.

“When Nelson Mandela became South Africa’s first democratically elected president, he was all too aware that apartheid had left the country with a deeply unequal health system, in which facilities and doctors are concentrated in the cities. So he appealed to Cuba’s then president Fidel Castro to supply doctors who could be deployed where they were needed. And he sent them [doctors] but told Mandela that South Africa would also have to train its own doctors in due course,” he continues.

Since the health department in South Africa doesn’t have the capacity to train doctors — it relies on universities, which are highly independent of government strategy, to do this — a deal was struck to send black students from mainly rural parts of the country to study medicine in Cuba.

“This was 1996 and there were nine of them — five from Mpumalanga and four from KZN. There were more, in fact, but a few dropped out due to culture shock. Cuba is a completely different country from South Africa, so I think it scared the hell out of them,” says Madela — yet several later asked to be sent back, “once they saw the others were making it”.

Bongile Mabilane, who has led two prominent research ethics committees in South Africa for the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and the Human Sciences Research Council, was the only female student in her 2002 Cuba cohort. She recalls sitting in the induction room and noticing “that the guy next to me was wearing the same clothes he’d had on when we boarded the plane — he was one of those that had come with just one suitcase”.

Mabilane feels there was a difference between the others and her.

“These kids came from hard circumstances in the rural parts of South Africa and they were serious about making Cuba work for themselves. They carried the South African flag so high and that pushed me to really start focusing on my books,” she says.

Nhlakanipho Gumede, a senior manager at Greys Hospital in Pietermaritzburg and former CEO of the iconic Pholela Health Centre, was one of those “one suitcase” students. He grew up in a village called Mbazwana in Umkhanyakude District in the northern parts of KwaZulu-Natal, completing his schooling in Ndumo, at the school where his mother taught.

FLYING HIGH: Arriving in Cuba, Gumede thought the place was “no different from downtown Durban, except that everyone speaks Spanish”, a far cry from his early idea that “the further I go, the nicer the place is going to be”. (Nhlakanipho Gumede)

FLYING HIGH: Arriving in Cuba, Gumede thought the place was “no different from downtown Durban, except that everyone speaks Spanish”, a far cry from his early idea that “the further I go, the nicer the place is going to be”. (Nhlakanipho Gumede)

He was only 16 when he went to Cuba but almost missed the flight because he didn’t have an ID or a passport.

“It took a lot of people to get me onto that Iberia Airlines plane. If my mother hadn’t run around on my behalf, I would have been stuck in South Africa doing I don’t know what,” he says.

Gumede, like all of the others interviewed for this article, had been studying something else before he was accepted into the Cuba programme — a business administration diploma at the Community and Individual Development Association in Johannesburg.

Nodikida had started a bachelor of science information systems, Mabilane was studying hotel management at Vaal University, and although Madela had started a medical degree at Medunsa (now Sefako Makgatho Health Sciences University), he dropped out in the second year for financial reasons and signed up for financial mathematics at the University of Pretoria — not because he felt called to actuarial science but because a portion of the tuition fee was discounted.

Says Madela: “Were it not for the [Cuba] programme, a lot of good people would have otherwise been lost to medicine in South Africa. I think this is part of the story.”

Black sheep

Mabilane, unlike most of her peers, was a city girl, “born and bred in Nelspruit, the last of six children”. Her parents were both “very religious”, and somewhat despaired of their youngest child, who was “quite the rebel”.

Speaking with the easygoing openness of someone who has found their anchorage in life, Mabilane recalls how she used to tell people she was going to “marry a rich guy” and that her sole reason for enrolling for a hotel management diploma “was to learn how to behave in hotels and restaurants, because you need to know that if you’re going to be rich”.

Her parents had other plans for her, though, and staged an intervention.

“They arrived on campus out of the blue, packed up all my stuff, and said, ‘We’ve stopped paying for this. You’re coming home.’ And they took me home to Nelspruit, half drunk.”

Mabilane’s mother was convinced God had spoken to her, telling her that her daughter was going to be a doctor.

“My mother said, ‘Let’s make a deal. If you fail, we will tell the church that this is the path that you have chosen, and we will cut our ties with you.’ I was over the moon, because the last thing I wanted on earth was to be stuck in the township, doing church.”

Back home, Mabilane’s sisters, now pastors themselves, called a three-day fast.

“Five or six women came, and on the second day an angel appeared and told them that they should not worry about me, that my future is secure, and that I will be known as a smart person.

“My sister dropped on the floor and had a vision of a plane, with me in it, and the aeroplane had legions of angels around it, and it was clear that the plane was heading overseas.”

FINDING YOUR PLACE: At first, Bongile Mabilane wasn’t keen on studying medicine — in Cuba of all places. But she could soon tell her parents: “Relax, medicine is the thing. I’m killing it.”

FINDING YOUR PLACE: At first, Bongile Mabilane wasn’t keen on studying medicine — in Cuba of all places. But she could soon tell her parents: “Relax, medicine is the thing. I’m killing it.”

Mabilane’s mother found out about the government’s medical training programme and applied on her daughter’s behalf — without telling her.

Mabilane chuckles at the memory. “She couldn’t have known that it was for Cuba, because when we learned that my application had been successful, she freaked and said, ‘My daughter doesn’t even want God and now she’s going to a communist country where they don’t even believe in God.’”

But Mabilane thrived in Cuba.

“In the first two years you do basic medicine, and because I was quite a high performer, I was selected to be in the ayudantia (“student support”) programme, where you’re paired with a specialist in training, what the South African system calls a registrar.

“I was allocated to this brilliant Cuban in the second year of his internal medicine residency, and literally became his shadow, following him on all of his rounds,” says Mabilane, who witnessed what she calls “the back-end of medicine” — the manner in which senior doctors relate to each other and go about their work.

“It’s a bit like being the child of parents who are successful in business, where you get to know the culture of business long before entering business yourself. It’s a very real headstart,” says Mabilane, who was able, in her fifth year, to tell her parents: “Relax, medicine is the thing. I’m killing it.”

Lost in translation

Many have spoken about the culture shock experienced by South African students arriving in Cuba for the first time but Gumede’s account is particularly memorable.

“When you’re a poor kid from a rural area and you’re catching a flight for the first time, you’re thinking to yourself, the further I go, the nicer the place is going to be. We transited through Madrid, and I‘m thinking, if this is Spain, where I am going is going to be quite something. And of course, when we got to Cuba it was, like, hang on, this is no different from downtown Durban, except that everyone speaks Spanish.”

Godisamang Kegakilwe, who is acting as the director for district hospitals and the coordinator for National Health Insurance for North West province, was part of the second cohort of students to arrive in Cuba, in 1998. The group wasn’t even aware that they’d be expected to study medicine in Spanish.

“That communication failure led to a 50% failure rate in the first year,” says Kegakilwe, who would painstakingly re-listen to recordings of his classes each afternoon.

The language gap would still be an issue for future cohorts, although Mabilane says, “We at least knew to pack our Spanish-English dictionaries.”

CUBAN CLASSICS: When Godisamang Kegakilwe’s group arrived in Cuba in 1998, he and his fellow students didn’t know that they’d have to study in Spanish, causing many students to fail in the first year.

CUBAN CLASSICS: When Godisamang Kegakilwe’s group arrived in Cuba in 1998, he and his fellow students didn’t know that they’d have to study in Spanish, causing many students to fail in the first year.

In Cienfuegos, where Mabilane was attending Universidad Ciencias Médicas Cienfuegos (South African students are split between several Cuban universities), she took the initiative of “paying the auntie who used to wash our laundry” for extra Spanish lessons at her house every Saturday, drawing from her monthly living allowance of $200 (around R2 200 at the time).

Kegakilwe’s answer was to throw himself into Cuban society.

“Cuban people are fiesta people, they enjoy themselves. So I was there with them in the bars, in the discoteca, and I would also visit Cuban friends on a farm in a rural area, by the riverside,” said Kegakilwe, the impact of his immersion still noticeable in the way he trills his r’s.

Although disorienting at first, the Cuban system was supportive, Kegakilwe recalled.

“At a very early stage the teachers identified students with difficulties and offered tailored support. In South Africa, if you don’t qualify to do medicine, then that’s that. But in Cuba you can come in and do it, and end up being one of the best students, because they consider where you come from, your language proficiency, any deficiencies or weaknesses, and they will assist you with targeted interventions,” he said.

Burning up on re-entry

South Africa’s Cuba students spend five years abroad and return to do the final year of their medical degree at a South African university. For most, the experience is harsh. In the early years, it verged on the intolerable.

Kegakilwe’s early group returned to limited choices of tertiary institutions.

“The very first cohort of students from Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal went to Walter Sisulu [University] and Medunsa, but when my group of 30 returned to South Africa at the end of 2002, the options included the universities of Pretoria, KwaZulu-Natal and the Free State.”

Manto Tshabalala-Msimang, the health minister at the time, “strongly discouraged us from going to UFS and UP [the universities of the Free State and Pretoria], due to concerns about the level of transformation and the acceptance of the Cuban programme.”

But Kegakilwe would not be dissuaded.

“We had that rebel radicalism that was in the air at the time in South Africa and so eventually the minister said, ‘Okay, but you can’t go alone.’ So I convinced a friend, Thabo Rampai, to join me. We felt that nothing could stop us, given what we had come through in Cuba,” says Kegakilwe, who better understood the minister’s warning during his first rotation at UP.

“The university had just transitioned from being a purely Afrikaans-medium institution and some of the professors were still resisting this and purely speaking Afrikaans. We did not reveal that we had studied in Cuba initially, because we feared judgment. But our inability to understand Afrikaans exposed us and then people were, like, ‘Ohhh, jy’s die kommuniste? [Oh, you’re the communists?]’”

Kegakilwe received no sympathy from Tshabalala-Msimang when he complained. “She said, ‘I told you not to go, but you went ahead anyway.’ And I knew then that we were on our own.”

But he prevailed and passed, as did his friend Rampai, who stayed on to specialise in surgery and is today one of the country’s top gastroenterologists. (Rampai now works in the private sector.)

Gumede describes the homecoming experiences as “a real mess”, highlighting what he terms “the language whiplash” of having to switch back from Spanish to English tuition.

“Most of us are from rural areas of South Africa and we weren’t confident in our English to start with. In Cuba, we had to learn Spanish in order to study, and by year four, our Spanish was better than our English. Yet in year six, back in South Africa, everything needs to happen in English again. It’s a problem,” he says, enunciating the words like an exhausted marathon runner.

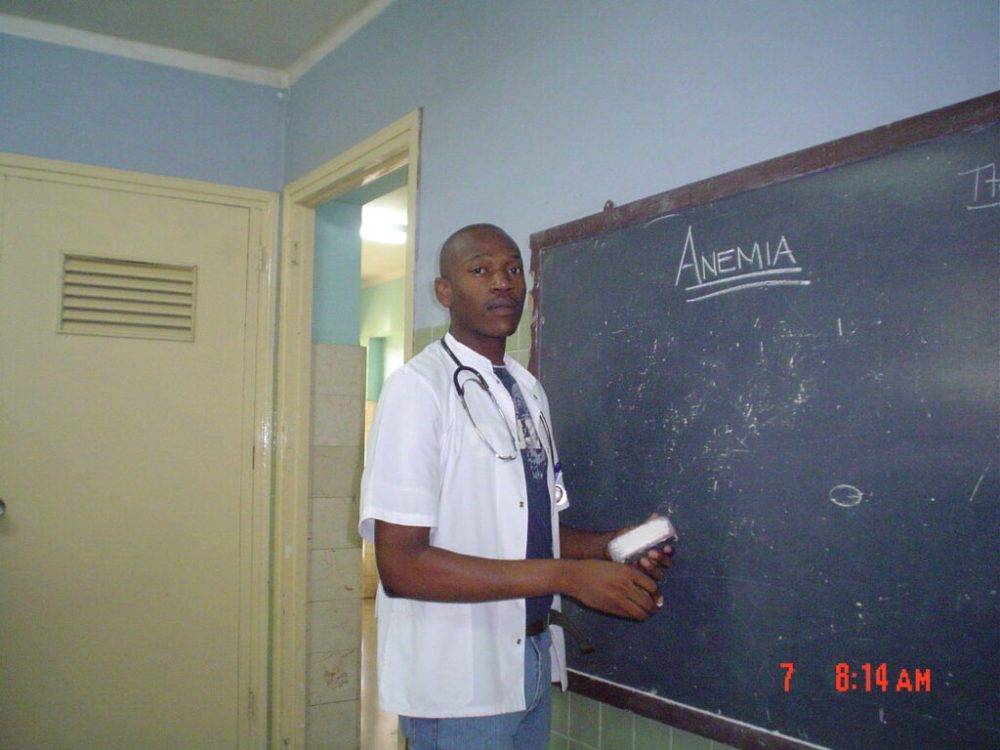

LEARNING CURVE: Nhlakanipho Gumede during the paediatric haematology block in his fourth year at Universidad de Ciencias Médicas de Villa Clara. (Nhlakanipho Gumede)

LEARNING CURVE: Nhlakanipho Gumede during the paediatric haematology block in his fourth year at Universidad de Ciencias Médicas de Villa Clara. (Nhlakanipho Gumede)

The demands of the transition proved too much for many of the students.

“A lot of the students were repeating twice, three times,” says Mabilane, who attended UP.

“Things like ‘you guys are half-cooked doctors’ were thrown around. We were told we didn’t know anything, that we were dumb, that we were just political pawns,” says Mabilane, who did not let on that she had studied in Cuba.

“My mother always says, ‘You pour the spices behind the kitchen door.’ In other words, you don’t reveal everything to everyone.”

She would go on to get two distinctions and was judged the best presenter in her cohort in internal medicine.

Many of those I interviewed made it very clear that, in the midst of all of the challenges, there were professors who were immensely supportive. Kegakilwe names Steve Reid, Ian Couper and Musa Mabandla. Gumede singles out Lionel Green-Thompson, now dean of the University of Cape Town’s faculty of health sciences, as someone who “helped us a great deal”.

“Every time I see him, I remind him of the valuable contribution he’s made in our lives. He always asks, ‘Where are you now?’ And when I tell him, his joy is so visible and sincere.”

Prevention, prevention, prevention

Cuban medical training is often described as being focused on prevention, unlike the South African system, which is more invested in the curative aspect.

“The training is pretty similar up until the third year, when an element of public health enters the Cuban curriculum. You’re told that a doctor doesn’t just stay in a facility; a doctor needs to be present in the community, understanding everything that’s going on — like how many people are living in each household, what type of diseases they have, what treatment they’re taking and so on — in order to come up with interventions that will actually be meaningful,” Gumede explains.

The emphasis on primary healthcare “doesn’t mean it’s a primary healthcare degree — it is a well-rounded medical degree”, he says.

According to one survey, 80% of South African students trained in Cuba return wanting to work in primary healthcare.

“You can understand why — it’s an impressive system,” says Madela, citing the fact that Cuba competes with richer nations in terms of health outcomes but with a fraction of the expenditure.

“Many of our students have had relatives who fell sick with diseases that could have been prevented with a more community-oriented approach, so the experience they have with the Cuban system, which emphasises prevention, is quite personal,” he says.

Kegakilwe recalls a phrase he used to hear in Cuba: Sin nada, hacemos todos.

“It means ‘with nothing, we do everything’. It comes from the time Cubans call el bloqueo, [the time of] the US embargo against Cuba. When I was there, they were sterilising needles and that sort of thing. They had no resources. That was Castro’s message to Mandela: instead of worrying about how to finance healthcare, rather identify the need and come up with a way to attend to it.”

On completing their studies, students of the Cuba programme must practise in South Africa’s public sector for five years — the quid pro quo for six years of free tuition. All of those interviewed attempted to carry the spirit of their Cuban training into their South African jobs. All encountered steep challenges.

“I got a lot of rejection, both soft and hard varieties,” says Mabilane, who landed a job at George Mukhari Hospital, north of Pretoria upon graduating.

“I had a patient with congestive heart failure on my first call during my cardiothoracic rotation, and when I wrote my notes about the management of the condition, the first page was dedicated to lifestyle modification.

The nurses said flat out, ‘We don’t write like this. Where do you come from?’ and gave me a prescription written out by another doctor. ‘Do it like this,’ they said. It hurt because the public health was just flowing out of me. I was, like, let’s get to the root of it, and instead I came up against this strictly curative approach,” she says.

Similarly, when Mabilane told a professor of cardiothoracic surgery that she wanted to be a public health doctor, after he asked her to join his fully male-staffed department, he did not conceal his disdain.

“He said, ‘You are such a waste. You could be saving lives but instead you’re going to study drains and sewage systems.’ And when I went to the province’s public health office to ask if I could shadow someone, like I’d done in Cuba, I was told, ‘No, wait for your internship to finish [and] do your community service. Go about things in the normal way.’

“I brought this inflexible South African mindset up in the speech I was invited to make at our graduation. The [health] minister at that time was Aaron Motsoaledi and I told him directly, ‘You’re losing a lot of great students by dictating how things should be and not fostering a culture that recognises and encourages initiative.’”

Bringing community healthcare back home

Kegakilwe’s path led back to Ganyesa in North West, the village he grew up in, and where he lives today.

“In Cuba, there were no resources. In South Africa, there are resources, but only in places — and Ganyesa is not one of those places.

There was no ATM, and the nearest Kentucky [fast-food outlet, Kentucky Fried Chicken] was 80km away. It is a challenging place to live, let alone work,” says Kegakilwe, who found that many of the clinics in his district were short of basics “like glucometers to test the blood glucose of diabetic patients”.

WORKING WITH LITTLE: “In Cuba, there were no resources. In South Africa, there are resources but only in places — and Ganyesa is not one of those places,” says Godisamang Kegakilwe of what he’s experienced in the North West, where he lives and works.

WORKING WITH LITTLE: “In Cuba, there were no resources. In South Africa, there are resources but only in places — and Ganyesa is not one of those places,” says Godisamang Kegakilwe of what he’s experienced in the North West, where he lives and works.

After looking at the community’s disease profile, he knew he wanted to work there, in primary healthcare. But the situation was untenable, he felt, and so he boycotted, staying away from work for a month.

In the same period, Kegakilwe attended and shared his story at the annual conference of the Rural Doctors Association of Southern Africa (Rudasa) — and duly became the organisation’s representative for North West.

“Being opinionated, you end up getting yourself into trouble,” he chuckles. Kegakilwe would become Rudasa’s longest-serving chairperson, helping to found the Rural Health Advocacy Project, which aimed to place rural issues on the national agenda.

During his internship year in Peddie in the rural Eastern Cape, Nodikida helped to found the Eastern Cape Cuban-trained Doctors Forum, which, although short-lived, promoted community diagnosis.

“We carried the message that, if you know what is wrong with the community, you’re able to plan accordingly and manage some of these diseases before they need to be cured, at great expense, at a tertiary healthcare centre,” he says.

Health for the people

As students, Nodikida, Madela and some others talked about setting up an organisation focused on primary care but it was Madela, who spent his internship and community service years in hospitals in KwaZulu-Natal’s uMzinyathi District, who followed through, founding an NGO called Expectra Health Solutions.

“In my first days on the job, I became alarmed by the complete absence of patient follow-up. In hospitals you treat, write the discharge summary and call for the next patient. Later, you hear the patient has died. Why? And why did that patient get sick in the first place?” says Madela, who started visiting communities on the weekends, checking in on some of the patients he had discharged from the hospital ward. His colleagues told him he was doing work below the station of a doctor.

“It didn’t bother me because we learned in Cuba that everybody participates, even if you’re a specialist,” he says, insisting that a doctor’s presence in the community helps to “take some of the mystique out of the doctor’s role”.

“In these communities, a doctor is someone you dress up to see. A doctor is someone you are afraid to disappoint, to the extent that some people are not altogether honest — they use tricks to dribble you into thinking that they are taking care of themselves,” he says, giving the example of patients with diabetes, who drink a lot of water on the day of their appointment, “hoping the doctor will mistakenly think that because their glucose levels are lower, they must be managing their condition well”.

Madela’s NGO attracted the support of powerful organisations, like the US-based Medtronic Foundation, and put tools such as glucometers and blood pressure readers into the hands of community healthcare workers. In 2017, he addressed the US House of Congress about noncommunicable diseases, and attended the World Health Assembly as a guest of the International Diabetes Federation. Madela said there was some irony in this recognition.

“It was like we were bringing this Cuban approach of working in communities to South Africa for the first time and yet the concept of community-oriented primary care started here in South Africa, in the 1940s,” said Madela, referring to the work of Sidney and Emily Kark, South African-born physicians, who in 1940 established a community health centre called Pholela, deep in rural KwaZulu-Natal, and for the next six years, according to one short history, developed “the concepts, methods, and program[me]s of applied social medicine for which they would later become famous”.

FOR THE COMMUNITY: Gumede’s passion for community-focused healthcare, as infused in Cuba, led him to eventually become the CEO of the Pholela community health centre in rural KwaZulu-Natal.

FOR THE COMMUNITY: Gumede’s passion for community-focused healthcare, as infused in Cuba, led him to eventually become the CEO of the Pholela community health centre in rural KwaZulu-Natal.

“In 2014, I was working at a district hospital in Creighton called St Apollinaris, and I came to know Pholela, which is in nearby Bulwer. I ended up working there as a medical officer, and as it was leaderless, I did what anyone who likes to see things working would do — I started managing,” says Gumede. He was eventually hired as Pholela’s CEO, “with a mandate to try to get the place back on the map, and beyond this to get the KwaZulu-Natal department of health to re-engineer primary healthcare”.

By all accounts, Gumede excelled in his duties, although he says the “re-engineering” of primary healthcare in the province remains a work in progress.

Says Gumede: “The Pholela model of community-oriented primary care has never really come back to the fore. There has been some progress, but the South African health system remains overly centralised and focused on cure rather than prevention.”

Forever Cuba

Almost two decades after graduating, the five profiled physicians are perhaps not as close to the primary healthcare mission as they once were, yet their affection for Cuba and its lessons remains undimmed.

Madela returned to Cuba and splits his time between Havana, Pietermaritzburg and his childhood home in Dundee.

Kegakilwe named his son Che Guevara and said his home “is a bit of a shrine” to the Marxist icon. “My son sometimes asks me, ‘But papa, why this name?’ and I tell him about my experiences over there, and how, if I could live one other person’s life, it would be Guevara’s.”

REMEMBERING A REVOLUTIONARY: Gumede at Plaza de la Revolución Ernesto Che Guevara, in Santa Clara, a tribute to Che Guevara’s enduring legacy as a revolutionary leader.

REMEMBERING A REVOLUTIONARY: Gumede at Plaza de la Revolución Ernesto Che Guevara, in Santa Clara, a tribute to Che Guevara’s enduring legacy as a revolutionary leader.

Gumede says his life mantra remains a philosophical statement he and his classmates were confronted with in their first year: El hombre piensa como vive, no vive como piensa. It means: “A man thinks as he lives, not lives as he thinks.”

Mabilane treasures a letter from her classmates before she left Cuba. “We all had this passion for public health but we knew we were going to get pushback in our respective countries, so they gave me this letter called ‘Yo maté al Che’, which means ‘I killed Che’, written from the perspective of the man who assassinated Che Guevara.

“My favourite line is: ‘Y que el hombre que de veras murió en La Higuera no fue el Che, sino yo.’ It means that a moral death is much more painful than a physical death, and the letter goes on to say that the man who really died that day wasn’t Che, but himself, the killer, because even though he killed a body, Che’s ideas are more alive than ever.”

Mabilane pauses: “I try to remember that whenever I’m faced with a moral choice in life.”

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.