Leaving a legacy: Preparing to close his door at UCT, Ntusi reflects: ‘I had given my all to this department, and to our work, and it’s time for somebody else to come and lead the department in a different direction.’ (Jay Caboz)

To get to Groote Schuur Hospital, one must at least travel some way on Cape Town’s Main Road, which runs between the two original enclaves of European settlement at the Cape — the Castle of Good Hope, built by the East India Company to defend its stake at the tip of the continent, and the naval base at Simon’s Town, which gave Britain’s Royal Navy supremacy in southern waters for a very long time.

The hospital complex, built on Cecil John Rhodes’s former estate, looms over the noisy road, its classical façade of Corinthian columns and Grecian urns amplified by Devil’s Peak.

When I arrive at 5pm, the benches outside the original hospital building, which are typically packed with patients, stand empty, and the late leavers among the staff are filing out of electronic access gates, making for their transport. A security guard with time on his hands offers to escort me to the elevators, down a hallway I had last walked 20 years before on a visit to The Heart of Cape Town Museum, which commemorates Christiaan Barnard’s 1967 achievement of what was then the holy grail of surgery: the heart transplant.

Symbol of excellence: Groote Schuur Hospital has been home to many of South Africa’s medical greats. Ntobeko Ntusi is among them. (Jay Caboz)

Symbol of excellence: Groote Schuur Hospital has been home to many of South Africa’s medical greats. Ntobeko Ntusi is among them. (Jay Caboz)

When I mention this to Ntobeko Ntusi, the person I’ve come to meet on J Floor, which houses the surgery department, he says “[it’s an] incredible achievement, but did you know that the world’s first prototype CT [computed tomography] scanner was built in this very same building about ten years before? Not many people do, and it’s arguably the more significant scientific breakthrough!”

Ntusi, who for the past eight years has led the University of Cape Town’s (UCT) department of medicine, overseeing 19 divisions and 18 research units, had been expecting an internet call but graciously welcomed me into his office. “I’m delighted, it’s much better this way,” he says.

Hung with a gallerist’s care on his office walls are an eclectic collection of artworks, including a vivid painting of two tango dancers, mid-calesita, and a Namibian desert scene.

“This one’s my favourite,” Ntusi says, picking up a small watercolour depicting steel-blue waters above a sky of the same colour as his tie. “It was done by my daughter.”

His next favourite artist, he says, is Amedeo Modigliani, the Italian-Jewish master famed for his portraits of women with elongated faces and necks. Ntusi says he read somewhere that Modigliani was influenced by African masks. Behind him, in a gold-leaf frame, is a distressing image: a crowd of Black men and women in front of a blue-green maelstrom. Some of the figures meet the viewer’s gaze with sock-puppet features; others face the void, arms raised and fingers pointing. It is not clear if the common emotion is seething rage, paralysing fear, or something else.

“It was painted for me by my very good friend, Bronwen Cotton, when I started in this job, in the midst of the student protests and the ‘Fees Must Fall’ movement,” Ntusi explains, adding that the piece was inspired by a press photograph of protesting UCT students outside Sarah Baartman Hall, which, at the time was called Jameson Hall, after Sir Leander Starr Jameson (prime minister of the Cape Colony from 1904, and who had led an unlawful raid in the former Transvaal in 1895, which sparked unrest and uprising in the country).

Ntusi was a member of the UCT council that announced the renaming in December 2018, which an official institution communiqué said “will help to more holistically reflect the history of all the people of our country”.

Transformation in the making

Below the painting, on top of a row of cabinets running the length of the office wall, is a pile of books — copies of a recently published biography of Bongani Mayosi, Ntusi’s predecessor as head of department, who took his own life in 2018.

The reasons for Mayosi’s death are not examined in the biography, but they were directly probed by the panellists of a 2018 university inquiry, which spotlighted the work pressures Mayosi experienced after the #FeesMustFall protests erupted in the faculty of health sciences early on in his tenure as dean, and hinted that the slow progress of transformation at the university had likely contributed to his death.

Ntusi would face many of the same pressures. His friend and colleague, Mashiko Setshedi (who will take over the reins from Ntusi from 1 July), had already told me that there was an undercurrent of concern for Ntusi’s wellbeing at the outset of his tenure.

“Not only was he one of our own — someone who had come through the ranks at UCT — but his appetite for work is legendary, and we had all witnessed how detrimental the pressures of the job could be,” she’d said.

Life and art: Paintings, photos and pictures adorn a wall above a bookcase in Ntusi’s office, a quiet reference to the many sides of this esteemed academic’s life. (Jay Caboz)

Life and art: Paintings, photos and pictures adorn a wall above a bookcase in Ntusi’s office, a quiet reference to the many sides of this esteemed academic’s life. (Jay Caboz)

Eight years on (a period which included the Covid-19 pandemic), Ntusi looks healthy, and projects an air of calm.

He takes a copy of the Mayosi book off the pile, and hands it to me. “He was wonderful, in every way. He had an emphatic, infectious laugh that made you instantly feel at ease.”

In the biography, the authors write that Ntusi was considered by many a protégé of Mayosi’s and several people I had spoken with, who knew both men, backed this up, describing several similarities in background, education, career path and character, some verging on the uncanny.

Ntusi smiles. “I wouldn’t encourage those comparisons,” he says, “but it’s true to the extent that we both grew up in the rural Eastern Cape, we both studied cardiovascular medicine at Oxford and we both led and cared deeply for this department.”

A new world

Ntusi was born in Mthatha, to parents Tembeka, a social worker, and Bubele, a teacher working for the department of education. He was the middle of three boys and remembers his childhood as being “incredibly happy and idyllic”, characterised by time spent outdoors. He was a reader — “my upbringing was punctuated by different books that made impressions on me at different times” — and somewhat of a loner and an introvert. He was (and remains, he says) extremely competitive.

“I mostly competed with myself. There were occasions where I would win and still feel unhappy, because I felt I hadn’t reached the goals I had set for myself,” he says.

“I think it’s been the same in my career in the sciences.”

One of the areas into which Ntusi poured his competitive energy was ballroom dancing, learning under a “wonderful dance teacher in Umtata by the name of Mr Tyesi”. At the age of 10, Ntusi was the national junior champion. “I may have peaked too early,” he says.

Although Ntusi moved between several different schools, spurred by his parents’ development of their own careers (his mother took a job at the [then] University of Transkei, and his father was promoted as inspector of high schools for the region), he remembers having teachers who were, without exception, “great role models, leading me to dream of becoming a teacher after school”. Wherever he went, Ntusi was “a bit of a teacher’s pet”, actively seeking interaction with his teachers outside of classes.

After his mother was offered the chance to do a doctorate in the United States, the family moved to Philadelphia. At Lower Merion High School in Ardmore, Ntusi battled with culture shock.

“The children around me were acutely aware of their images. I spoke with an accent and dressed funny. Having come from apartheid South Africa, I had this expectation of kinship with Black American students but in fact I found it very difficult to make meaningful connections at the time,” he says, adding that most of his peers and his friends were white American children. “It came as a shock, because I had never had that type of experience growing up as a Black South African in the Transkei.”

Eureka!

A video about childbirth screened in a science class led to Ntusi’s “first eureka moment in life”.

“I sat among this group of pubescent children, hearing all these immature jokes, and I decided right then that I wanted to go to medical school, to study towards being an obstetrician, so that I could contribute towards bringing new life into this world, marvelling daily at the beauty and mystery of childbirth,” he says, playing up his youthful earnestness.

From the US, Ntusi applied and was accepted to study medicine at UCT, but his application to Haverford College, a private liberal arts college in Philadelphia, was also successful, and he decided to stay on in the US, doing a double degree in molecular and cellular biology, and medical sociology.

Ntusi admits to being “a bit of an academic glutton”, who took additional courses in fine art, art history, organic chemistry and philosophy. He doesn’t mention any athletic pursuits, but in my preparation for the interview I had stumbled upon a 2021 article on the Haverford Athletics webpage, celebrating Ntusi’s achievements in this area. As a member of the cross-country team, Ntusi “won the Centennial Conference Individual Championship during the 1997 season and finished as the runner-up at the Mideast Regional”. On the track, “Ntusi was an indoor conference champion in both the mile and 4×400 relay … He would additionally win individual gold medals at the outdoor conference championships in both the 1 500 metres and the steeplechase while competing on back-to-back 4×400 and 4×800 metre championship relays.”

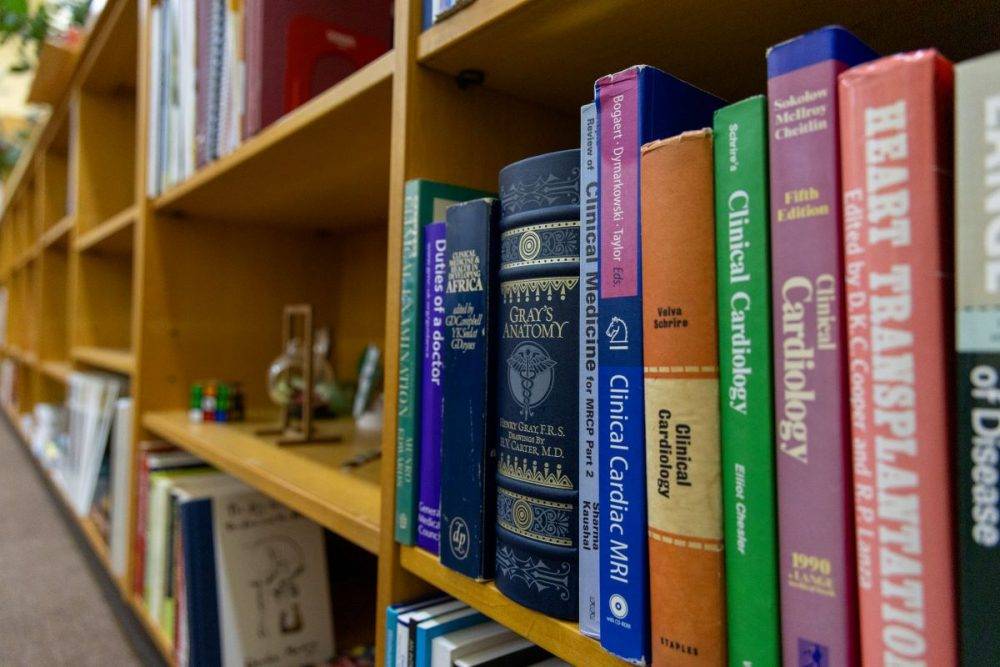

‘An academic glutton’: Filled bookcases line the walls of Ntusi’s office, testament to his love of learning. (Jay Caboz)

‘An academic glutton’: Filled bookcases line the walls of Ntusi’s office, testament to his love of learning. (Jay Caboz)

When confronted with this evidence, Ntusi says, “I really thrived at Haverford”, and then wrests the conversation back to academics: “It was also the place where I learned the scientific method, and how to critically appraise scientific literature.”

Going back home

For his honour’s thesis, Ntusi “looked at the role of tissue transglutaminase as a downstream pathway for mediating apoptosis or programmed cell death”, which to my unscientific ear sounds like an oration of contra-indications. Noting my incomprehension, he chuckles and says, “It was a very interesting project at the time.” (Transglutaminases are a group of enzymes and some types are specifically at work when cells start to die.)

If there is a walking advertisement for the broader liberal arts approach to education, it is Ntusi.

His erudition, and ability to discuss a range of topics with the same fluency and insight, whether Expressionism or endocarditis, seems to belong to an age in which professionals were their nations’ leading intellectuals.

Contemporary South African professionals, by contrast, and perhaps medical professionals especially, are often criticised for being a bit blinkered — products of a system that delivers matriculants into professional degrees and specialisations defined by rote learning.

After finishing at Haverford, and with a prestigious National Collegiate Athletic Association scholarship in his pocket, Ntusi applied again to study medicine at UCT, and thought he had better call the dean of health sciences at the time, Nicky Padayachee, to explain why he hadn’t taken a place the first time he was offered one.

“It was a Thursday afternoon and he said, ‘If you come to my office at seven o’clock next Tuesday, we can talk,’ and so I jumped on the next plane and came to Cape Town. I was outside his office at six o’clock, but he had forgotten about me, and only came for a meeting at nine. I started to tell him about myself and in less than a minute he said, ‘Okay, we’ll accept you.’ It was the most expensive interview I’ve ever had.”

In love with medicine

Ntusi was “delighted to come back home” and set his sights on getting to fourth year, at which time he would rotate in the labour ward.

“It was the whole reason I was studying medicine, and I could hardly sleep the night before. By the end of that day, however, I’d had my second eureka moment — and it was one of great disappointment.” He recalls being “appalled by the [sound of] screaming mothers, and the smell of bodily fluid all over the labour floor”.

“I just knew obstetrics was not for me, and had it not been for the encouragement of my parents, I probably would have quit medicine at that point.”

His next rotation would be internal medicine, and it, too, was epiphanic.

He says: “I fell madly in love. I just loved the sense of inquiry — how, with a well-taken history, the application of clinical skills and by using your every mental resource, you can figure out complex medical problems, all in service of the patient who suffers.”

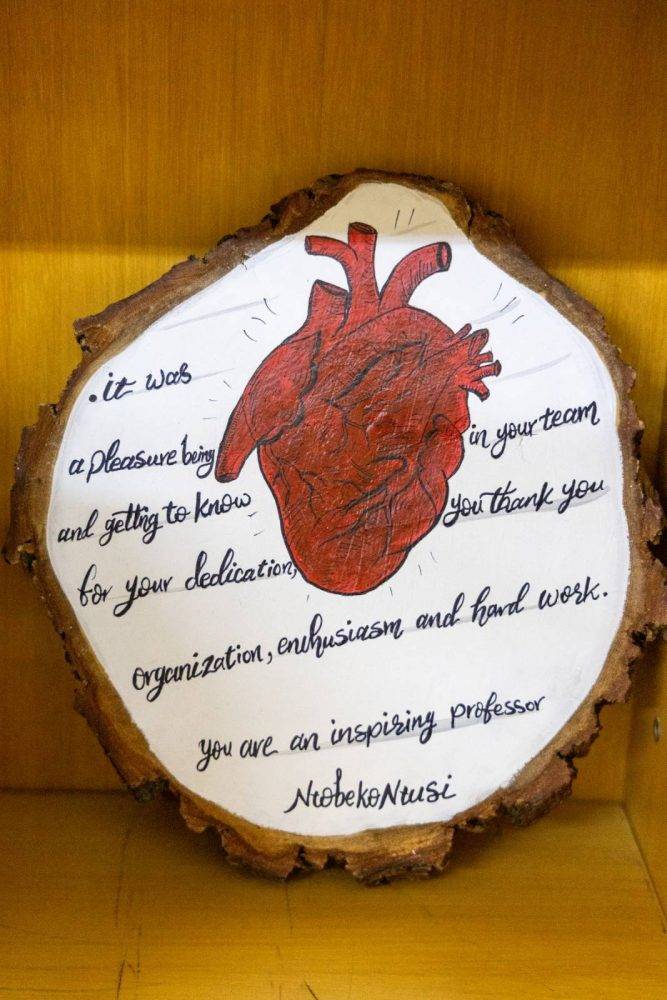

Mentor with a heart: ‘Behind every good researcher is a great mentor, and Ntobeko exemplifies this role impeccably,’ says former student Petronella Samuels, now head radiographer at the University of Cape Town. (Jay Caboz)

Mentor with a heart: ‘Behind every good researcher is a great mentor, and Ntobeko exemplifies this role impeccably,’ says former student Petronella Samuels, now head radiographer at the University of Cape Town. (Jay Caboz)

Ntusi worked out his internship and community service years close to home, at Frere Hospital in East London, before returning to UCT to train as a specialist physician. He also registered for a medical doctorate, looking at the genetics of heart muscle (cardiomyopathy), under the supervision of Bongani Mayosi.

“He had an incredible mind, manufacturing ideas nonstop, and he had a way of making you feel like those ideas were yours. In fact, some of my current research is in areas that we started working on together almost 20 years ago,” says Ntusi, who “whizzed through” his training as a specialist, “rotated” for three years, and then proceeded to write up his doctoral thesis.

Ever eager for learning and advancement, he also applied for the Oxford Nuffield medical fellowship, and was awarded it. Ntusi did a second doctorate in cardiovascular imaging at Oxford, and upon completing his studies returned to UCT to do his clinical training in cardiology.

Within a fairly short span of time, Ntusi had completed his specialist training, and had a number of peer-reviewed articles under his name. He sat on working groups of the World Health Organisation and the United Nations, led committees of a number of international societies, and the list of master and doctoral students he had supervised was growing.

“He is probably one of the most strong-willed people I’ve ever met. You’d have to be to set up South Africa’s first cardiac MRI [magnetic resonance imaging of the heart] service, where state-of-the-art clinical and research work combines methodically in a way most centres around the world would be jealous of,” says Anna Herrey, a consultant cardiologist at Barts Hospital in London, who compared notes with Ntusi during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Mpiko Ntsekhe, the current head and chair of UCT’s division of cardiology, points out that “Ntobeko has very much taken after his renowned mentor Bongani Mayosi, and spread his research wings”, adding that, “as one of very few cardiac MRI specialists on the continent, he has very effectively used this very unique sophisticated technology to study and understand cardiovascular disease mechanisms, pathophysiology, pathology, patterns of injury natural history and response to treatment.”

Peer review

By all accounts, Ntusi remained grounded.

Pennsylvania-based cardiologist, Ron Jacob, who met Ntusi while serving on the board of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, recalls being impressed by an interaction between Ntusi and a patient.

“When a patient in a scanner needed an intravenous line [a thin tube inserted into a vein for delivering fluid or medicine directly into the blood], he did it himself, without hesitation, instead of waiting for a nurse to come and do it. A lot of people in his position lose touch with life at a patient care level,” said Jacob.

A doctor at heart: Despite being head of department, Ntusi never stopped being a doctor first. (Jay Caboz)

A doctor at heart: Despite being head of department, Ntusi never stopped being a doctor first. (Jay Caboz)

Petronella Samuels, who was supervised by Ntusi during her master’s degree in diagnostic radiography, described how he helped her to overcome a lack of confidence. “I felt inadequate around colleagues with extensive medical knowledge, but his unwavering support and guidance shifted my perspective. He encouraged me to embrace my role as a knowledgeable radiographer within my field of specialisation, and inspired me to continually strive for excellence in my field.”

When seniors in the UCT medical department asked Ntusi to consider applying for the position of chair and head of the department, he initially rebuffed them, preferring to focus on building his research career — “my main academic love at the time”. But he did increasingly think about the kind of department he would like to lead, “and at the last minute I decided to throw my hat in the ring”.

Ntusi “applied on a ticket of five things” that he wanted to achieve, all aimed at building a more efficient and accountable department with a healthier, more supportive culture. His appointment proved to be a boon for an institution in considerable flux.

“He’s been a great leader,” says Setshedi. “[He was] amazingly supportive, without being a loud and bubbly type. He gave us our autonomy, doing away with some of the more finicky reporting traditions and never micromanaging”.

Ntusi has “led from the front, both in deed and word”, adds Ntsekhe.

During his tenure, the number of Black clinicians and faculty at UCT has increased. In a Harvard Public Health article on transformation in South Africa’s medical schools, Ntusi is quoted as saying that “Black excellence [has become] both normative and cool”. “People are now no longer debating whether the institution is transformed, but how we work collaboratively to be where we need to be,” he’s quoted in the piece.

Setshedi corroborates these claims. “It’s just an easier place to be,” she says.

Herrey, on a visit to Groote Schuur, was struck by the fact that “everyone seemed to know him, and he seemed to know everyone too, most of them by name: the lady in the tuck shop, the receptionist in the clinic, the man sweeping the stairs, the doctors and the medical students and even some of the patients we passed in the corridor.”

‘They’re lucky to have him’

After three years as head of department, Ntusi began to wonder if he had been ambitious enough, as most of the goals he had set had been accomplished. He and his team were shortly consumed with responding to the Covid-19 pandemic, but as South Africa “headed out of Covid” Ntusi embarked on a consultative process aimed at trying to redefine what his department’s priorities should be.

This led to his most recent eureka moment.

“I realised that I had given my all to this department, and to our work, and that maybe it was time for somebody else to come and lead — not only this process of developing a new set of priorities but to lead the department in a different direction,” he says, admitting that he liked the idea of stepping out of Groote Schuur on a high, which, according to Ntsekhe, he most assuredly is.

“For many of the years that he’s been at the helm, the department of medicine has been consistently recognised not only as one of the most productive at the university but also the most transformed [according to the university’s scorecards]”.

When an opportunity to apply for the position of president of the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) came up, Ntusi went for it. His appointment was announced in early January, and he will take up the position on 1 July.

“I’m thrilled,” he says, “I think the SAMRC is a wonderful science council — big enough to do work that matters, and small enough that it can change. The culture feels familial, and there’s a strong drive to have an impact.”

Looking ahead: After eight years as the head of medicine at UCT, Ntusi is ready for new opportunities at the SAMRC, ‘a wonderful science council — big enough to do work that matters, and small enough that it can change’. (Jay Caboz)

Looking ahead: After eight years as the head of medicine at UCT, Ntusi is ready for new opportunities at the SAMRC, ‘a wonderful science council — big enough to do work that matters, and small enough that it can change’. (Jay Caboz)

Colleagues of his that I’ve spoken with think the move is a good one.

“They’re lucky to have him — he’s such a good researcher,” says Setshedi, adding that the general feeling in the department is that eight to 10 years is, today, the healthy timeline for tenure for the head of department position. “I think Ntobeko’s choice is smart, both professionally and in terms of his general wellbeing,” she says.

Groote Schuur Hospital is often said to exist “in the shadow of Table Mountain” — indeed this was the title of the first history of UCT’s medical school.

Ntusi appears to be stepping out of that shadow a stronger person and professional, having done his part to maintain and enhance his department’s reputation for scientific excellence, while improving its humanity.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.