A restaurant owner counts money by candlelight. Photo: Leon Sadiki/Getty Images

Public enterprises: The ANC’s heart of darkness

State capture is often cited as the the reason for the department’s ongoing failures, but its problems run far deeper

GRADE: E

In 1996, South Africa’s first minister of public enterprises, Stella Sigcau, found herself at the centre of what journalist Mpumelelo Mkhabela describes in his book The Enemy Within as the ANC’s first moral test.

An allegation of corruption against Sigcau culminated in the expulsion of her accuser, Bantu Holomisa, from the governing party.

Of this episode, Mkhabela writes: “Steeped in an exile culture of guarding party secrets at all costs — which was quite understandable in the days of the struggle given the risks of apartheid infiltration and destabilisation, but incompatible with the democratic culture it had promised to deliver — the party was concerned above all with self-preservation.”

The National Consultative Forum, the precursor to Holomisa’s United Democratic Movement, accused the ANC of accepting corruption “as a way of life”.

Many years later, after the minister’s death, the department Sigcau led became the broker of some of the most pernicious state capture-era deals.

Stella Sigcau

1994 – 1999

Stella Sigcau

1994 – 1999

Today, in the wake of a seemingly Sisyphean effort to rehabilitate the country’s state-owned entities, this legacy of corruption is often blamed for the department’s ongoing failures. But the seeds of the department’s downfall were probably planted long before state capture sunk its teeth into it.

Under Sigcau, the department served more as an office for the privatisation of the country’s state-owned entities, although she never really managed to set this in motion.

In 1999, The Economist ran an article headlined “The painful privatisation of South Africa”. It described Sigcau as “regal but undynamic”, noting that she failed to inspire markets.

The fledgling government inherited a number of state entities, established by the apartheid administration to develop a stable industrial base for white rule. The ANC was also saddled with a huge amount of apartheid-era debt and selling public assets would relieve the state of liability.

But, by 1999, the government had privatised only roughly R11 billion worth of its assets. What was left of the country’s state-owned entities were estimated to be worth R150 billion at the time.

Like The Economist, the Mail & Guardian couldn’t resist referring to Sigcau’s Xhosa lineage when assessing her performance, questioning whether this was the only reason for her having held on to the job for so many years. “Many opportunities for privatisation — her brief — have been squandered over the past five years,” the minister’s 1998 report card read.

Jeff Radebe

1999 – 2004

Jeff Radebe

1999 – 2004

The M&G surmised Sigcau would not survive incoming president Thabo Mbeki’s knife and, to the relief of the markets, she did not.

Despite his ties to the South African Communist Party (SACP), Sigcau’s successor, Jeff Radebe, was given The Economist’s blessing on account of his hit-the-ground-running approach to privatisation. Within his first six months in the portfolio, Radebe vowed to sell R150 billion in state assets by 2004.

Among the entities in Radebe’s crosshairs were Abakor, the state abattoir operation — which was eventually liquidated — as well as the South African Forestry Company Limited and Alexkor, the state-owned diamond company. The latter two companies remain in the state’s storehouse to this day. Radebe did see through the sale of a 20% stake in SAA to Swissport. But the state ended up having to buy these shares back just two years later.

Radebe’s biggest coup was the partial listing of Telkom, which went through despite strong opposition from his SACP and fellow ANC ally, trade union federation Cosatu.

The department of public enterprises was guided by a policy document released by Radebe in 2000, which replaced the word “privatisation” with the more palatable “restructuring”.

Barbara Hogan

2009 – 2010 (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Barbara Hogan

2009 – 2010 (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Importantly, the document set out how restructuring would be undertaken at power utility Eskom and state logistics company Transnet, both of which were considered strategic state assets.

Despite this, the pair — which would eventually become the two biggest targets of state capture, as well as huge threats to the country’s economy — have remained largely unchanged until very recently.

Many will point to political wrangling, and labour’s resistance, as

the reason for the delays in restructuring Eskom and Transnet.

In 2003, the government began to revise its plans to privatise part of Eskom’s generation assets, although the utility’s restructuring was still on the table. This was solidified after the ANC’s win in the 2004 elections, when the party said it would not sell Eskom’s core assets.

That year, Alec Erwin, who had taken over from Radebe, announced the wholesale sell-off of state-owned assets was off the table, adding that labour would in future be consulted on the restructuring of state enterprises.

Erwin — who, during his previous job as minister of trade and industry, played a fundamental role in the sale of state steel company Iscor — also floated the idea of public-private partnerships for Eskom, Transnet and arms supplier Denel. The proposal was rebuffed by Cosatu.

But Erwin’s time as public enterprises minister was more important for another reason, insofar as it exposed a fundamental flaw in the state’s approach to state-owned entities: that it had failed to invest in them despite the demands of a growing economy.

This under-investment, which would have monumental consequences down the line, was largely a symptom of state-owned entities being expected to be self-sufficient, despite also having to fulfil a developmental mandate which all too often flew in the face of their commercial aspirations.

Malusi Gigaba

2010 – 2014

Malusi Gigaba

2010 – 2014

For example, for the first seven years after Eskom was formed in 1923, the utility was capitalised by government advances, subsequently converted into treasury loans with terms of up to 40 years. After 2001, however, Eskom had to raise its own revenue through tariffs as well as the debt market. The utility also lost its tax-exempt status.

Meanwhile, Eskom has to raise revenues from tariffs the utility contends are too low, as well as provide electricity to a consumer-base that can’t afford to pay.

The recently leaked draft Roadmap for the Freight Logistics System in South Africa — which sets out the state’s new plan to rehabilitate Transnet — admits that this approach was flawed, noting: “While the corporatisation of SOEs [state-owned entities] was intended to enable them to remain agile and responsive to changing business environments, they have largely failed to keep up with the evolving dynamics of the sectors in which they operate.”

But by the time the government admitted that it had erred in its failure to invest, in this case in Eskom’s generation infrastructure, South Africa was about to be plunged into the mayhem of state capture.

This era would undermine the credibility of the state, gnaw at its capacity and shatter the ideal of a government as the trusted guardian of the public purse. Add to this a financial crisis, and the battle for state resources was bound to get ugly.

Following Brigitte Mabandla’s brief stint at the ministry during Kgalema Motlanthe’s ad hoc government, the department was entrusted to Barbara Hogan who — after having spent the best part of a decade in jail and facing down Mbeki over the HIV/Aids scandal — was considered unimpeachable.

But Hogan’s time at the department would be short-lived.

She’d been handed a poisoned chalice. Eskom’s finances were in trouble, as it endured the first blows of load-shedding. Other state-owned entities weren’t much better off. Even Transnet, which was relatively insulated from the chaos by Maria Ramos and a strong board, was buckling under ongoing operational inadequacies, particularly in its crucial freight rail division.

Management succession battles at Eskom and Transnet, symptoms of the deeper war over resources, would end up being Hogan’s undoing.

Then president Jacob Zuma made quick business of getting rid of Hogan after the two had a dogfight over governance at state-owned entities. Between them, the two ministers that followed — Malusi Gigaba and Lynne Brown — had eight years, during which billions were syphoned from Eskom and Transnet and governance left in tatters.

Lynne Brown

2014 – 2018 (Photo by Thulani Mbele/Sowetan/Gallo Images/Getty Images)

Lynne Brown

2014 – 2018 (Photo by Thulani Mbele/Sowetan/Gallo Images/Getty Images)

The department Pravin Gordhan inherited was a shadow of its former self. Not only had state capture gutted state-owned entities, but it also made working in government an unattractive prospect. Lives were ruined, technocrats tormented and reputations sullied.

But who better to take on the job of turning the ship around than the man who rehabilitated the South African Revenue Service?

It eventually became clear, however, that whatever magic touch Gordhan had in a previous life was basically powerless in this one. The minister’s efforts to restore governance at state-owned entities started to feel heavy-handed, earning him a reputation as a meddler.

Gordhan, meanwhile, raised red flags over a second round of state capture, evidenced by resistance to reforms.

Despite accusations that Gordhan has done little to turn around state-owned entities — it is true that many are in a far worse position than when he started his term — he has managed to bring about more reform than any of his predecessors.

The restructuring of state-owned entities has been controversial and even, in the case of the SAA sale, scandalous.

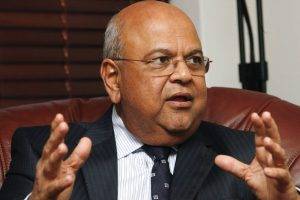

Pravin Gordhan

2018 – present. Photo: Bongiwe Gumede/Gallo Images/Foto24

Pravin Gordhan

2018 – present. Photo: Bongiwe Gumede/Gallo Images/Foto24

Perhaps the minister best at enduring a flogging, Gordhan’s time at the department has landed him on the receiving end of sometimes seething criticism. The ANC has even called for his department’s dissolution.

But Gordhan may still get the last laugh, with one of his final moves under the current administration being to put in motion the transferral of state-owned entities out of the department and into a holding company.

If successful, Gordhan will have radically changed how state-owned entities are managed — though it remains to be seen whether this will be for the better, or will land us in the mud again.

The department scores an overall lowly E.

Get the M&G’s take on other ministries over the past 30 years:

Department of Health

Department of Police

Department of Finance

Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment

Department of Human Settlements

Department of Justice and Constitutional Development

Department of Education