Drought-stricken: The dry vista around Bloemhof and Geluk farms, bordering on the Namib-Naukluft National Park. Photo: John Grobler

A group of Namibian and German entrepreneurs are developing a new smelting technology using green hydrogen that aims to reduce the negative effects of steel production. Globally the steel industry is estimated to contribute three million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, or about 9% of global emissions.

“It became very clear that Namibia is badly affected by climate change … with the droughts causing long-term negative effects,” said HyIron chief executive Johannes Michels, a German-Namibian who returned to the country of his birth to take over the family’s farming business 15 years ago.

Together with his partners, HyIron identified steel production as a major but largely ignored aspect of global warming and set about finding a way to produce carbon-free steel as a potential business opportunity.

Their big break came when their proposal for carbon-free steel was successful in a clean energy competition issued five years ago by the regional government of Lower Saxony, a state situated in northwestern Germany, Michels said.

The project is funded by a €13.6 million (about R280 million) grant from the German Federal Ministry of Economics and Climate Protection. It is located on Farm Bloemhof, about 80km inland from the port of Walvis Bay and is expected to be fully operational by the end of 2024.

According to Michels, their proprietary-sealed rotary kiln technology was developed in conjunction with German partners in Lensing, where the first proof-of-concept plant was built. It will produce no waste and, more importantly in drought-stricken Namibia, only use a small amount of water that will be continuously recycled.

Kelvin Amukwaya, project engineer: HyIron is currently building its first-phase solar plant of 25MW. Photo courtesy HyIron

Kelvin Amukwaya, project engineer: HyIron is currently building its first-phase solar plant of 25MW. Photo courtesy HyIron

Low water

For a former farmer like Michels, this low water requirement is a major selling point in an area that has very little water or any large natural aquifer that can be tapped. Every other green hydrogen project in Namibia will have to construct their own desalinations plants that — environmental impacts aside — can cost as much as $300 million to $400 million, a major upfront expense for a start-up project such as this.

“We will need at most a tanker of water per week that we will bring in from Arandis”, about 40km away from the project site, he said.

About 450 litres of fresh water is required to produce 1kg of steel using green hydrogen. According to University of Cape Town energy expert Hilton Trollip, it is theoretically possible to set up a production facility with a closed loop water system. He advised that although this technology exists, it has to date not been tested at scale, and will be costly.

HyIron’s Project Oshivela — the Oshiwambo word for iron — is building its first-phase solar plant of 25 megawatts to power the first kiln to be installed. In its final form, the plant will be powered by an 18MW wind and 140MW solar plant.

Michels said the plant will only operate during day-light hours, when it is expected to generate enough renewable energy to produce about five tons of carbon-free steel an hour. Production of 27 000 tonnes of green steel is planned over the first 3 000 hours of this phase.

As for feedstock, HyIron is looking at various options, including sourcing magnetite and hematite from the Lodestone mine, a privately owned mine about 30km out of Dordabis east of Windhoek. Initially, they plan to use scrap steel to produce carbon-free briquetted steel to prevent oxidation of the final product, Michels said.

The construction phase will create 200 jobs, and HyIron expects to employ 50 permanent staff once the project goes into operation in November, he said.

Its low operational cost could provide the economic impetus to Lodestone, a high-grade but relatively small deposit that has struggled to compete in the international market, to develop into a fully-fledged 24/7 operation employing hundreds of people, suggested one of the smaller Lodestone shareholders.

Premium-priced product

So far HyIron has not signed up any clients for their steel product, but there is a lot of interest from German heavy industry looking to take advantage of carbon-credit trading schemes to off-set the cost of what will be a premium-priced product, Michels said.

This was still an untested market, he added: the only other company pursuing the same route is Swedish steel producer SSAB, which is looking to produce five million tonnes of carbon-free steel by 2030 by exclusively using hydropower.

Michels said HyIron is not sure what its product will cost, and the price will be set by whoever enters this market first with big enough volumes to create enough demand for carbon-free steel to be economically sustainable.

HyIron will be the only steel producer that exclusively uses renewable energy for producing carbon-free steel, and as such expects their product to command a price premium. To that extent, he expected HyIron to set the price for as long as they enjoy this market position, he explained.

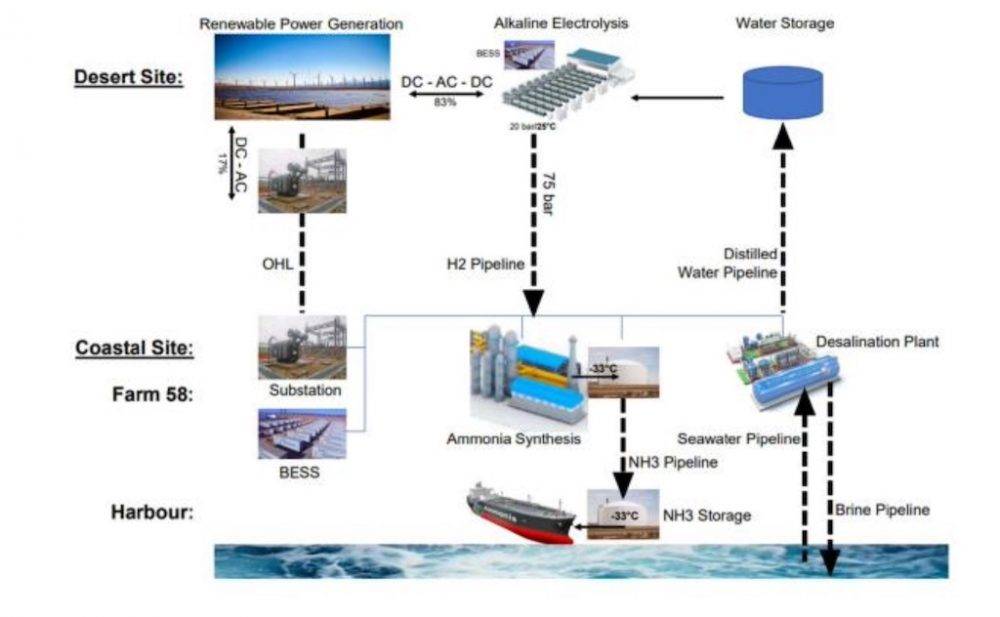

Many moving parts: Schematic illustration of the green hydrogen scheme being developed by CMB.Tech and Clean Energy Solutions. Graphic supplied

Many moving parts: Schematic illustration of the green hydrogen scheme being developed by CMB.Tech and Clean Energy Solutions. Graphic supplied

Ammonia fuel

On the neighbouring farm Geluk, a joint venture is developing a solar and wind farm for a project that aims to produce ammonia fuel for shipping and rail transport. But it appears to have stalled.

Of nine green hydrogen projects under development in Namibia, this has generally been regarded as the most promising because of the involvement of local private capital, according to independent energy consultant Detlof von Oetzen. It is a joint venture between Belgian maritime company CMB.Tech and local agro-industrial giant Ohlthaver & List’s Clean Energy Solutions.

Unlike HyIron’s stand-alone design, this project has many moving parts: a solar- and wind-powered alkaline-based hydrogen plant on Geluk. It is to be linked by a 75km power line, a high-pressure hydrogen pipeline and a water pipeline pumping distilled water up from the coast in order to supply the hydrogen plant.

According to its environmental impact assessment report, the project plans to generate renewable energy to power a yet-to-be-commissioned coastal desalination plant that will supply the inland hydrogen plant, which will in turn pump ammonia down to the hydrogen refuelling station.

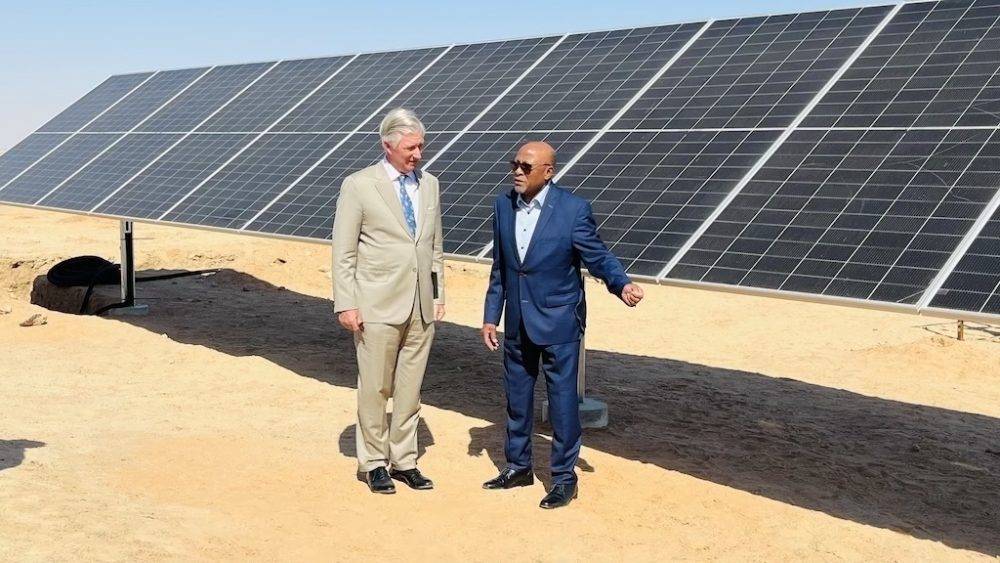

State visit: Belgium’s King Phillippe (left) and Namibian President Nangolo Mbumba inaugurated the hydrogen station on Farm 58 in February. Photo: Eveline de Klerk

State visit: Belgium’s King Phillippe (left) and Namibian President Nangolo Mbumba inaugurated the hydrogen station on Farm 58 in February. Photo: Eveline de Klerk

Clean energy market

This hydrogen station on Farm 58, about 10km outside Walvis Bay, was inaugurated during a state visit by Belgium’s King Phillippe in late February. The Belgian interest in Namibian green ammonia appears related to King Phillippe’s investment in shipping, and with Antwerp being a major energy hub for central Europe, could see ammonia fuel gain traction in the clean energy market, said economist Roman Grynberg.

The project at Farm 58 is not only one of many moving parts, but also of many partners (CMB.Tech, Clean Energy Solutions, Elof Hansson Green Hydrogen Namibia and Powerplay Investments) who appear to be in some dispute at the moment, said Institute of Public Policy Research executive director Graham Hopwood.

The infrastructure costs are formidable: a desalination plant large enough to supply enough water to produce two millions tons of ammonia annually, with the water having to be pumped 75km inland — and uphill — to the hydrogen plant on Farm Geluk, in addition to a high-pressure hydrogen pipeline to deliver the hydrogen to CMB.Tech’s ammonia plant on Farm 58, and a powerline to bring enough electricity from Farm Geluk down to the coast to power both the desalination plant and ammonia production facility.

“There appears to be some disagreement on how to meet development costs,” Hopwood said in a brief telephonic interview. CMB.Tech and Clean Energy Solutions did not respond to requests for comment.

UPDATE: CMB.Tech and Clean Energy Solutions reached out post-publication to clarify that even though they are using the same Walvis Bay sites as Elof Hansson Green Hydrogen, there is no relationship between these two companies or their projects. The next article in the series will clarify this to the full extent.

John Grobler is a Namibia-based associate at Oxpeckers Investigative Environmental Journalism. This investigation is part of a #PowerTracker series on green hydrogen, supported by the Heinrich Böll Foundation.