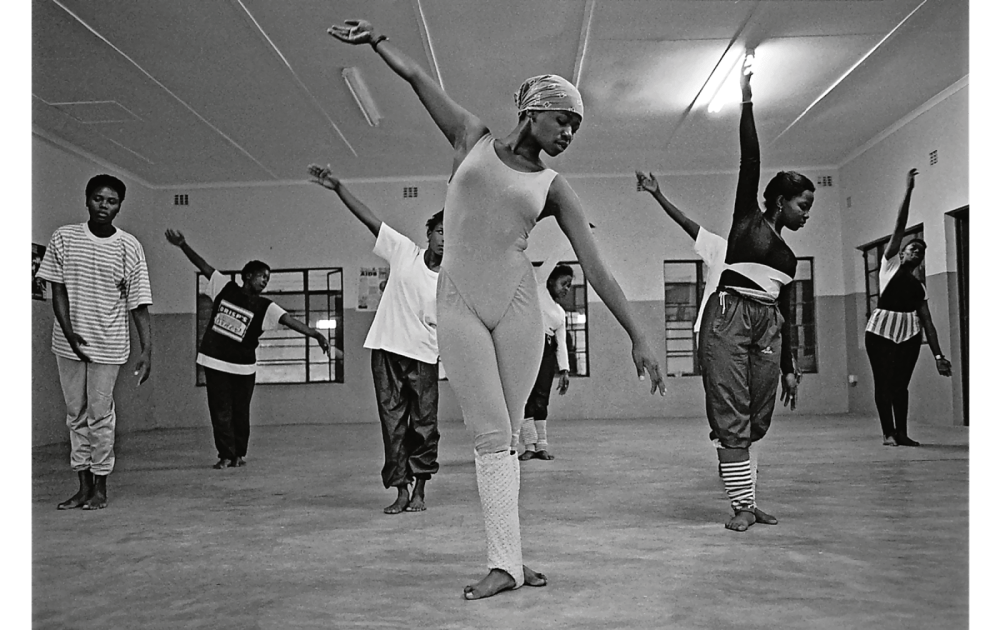

Returning the gaze: Lebogang Tlhako’s image forms part of the Reflections: On Black Girlhood exhibition

A 30-minute drive west of Estcourt is a small village called Emangweni. Emangweni is characterised by its reddish soil, which gives way to crater-like potholes in the rainy season. The sounds and smells of Emangweni animate my earliest memories of girlhood. Deep into the hilly KwaZulu-Natal terrain are the homes built by maternal and paternal grandparents.

Memories, like words, can often be unstable purveyors of truth, as African American writer Kiese Laymon has argued. So, in a reach for certainty, I often look at old images of my mother and her sisters to recalibrate my memories of Emangweni.

My maternal aunt, who in isiZulu is quite literally my “younger mother”, is photographed in her Sunday best as a young girl. No doubt the white satin dress she poses in is a prized possession from a boutique called Brokenshaws on the main road in Estcourt called Harding Street.

This portrait of a young black girl playing at womanhood is an image I have replicated in my own photographs as a young child. Hands on my hip, lips pursed and an exacting gaze right back into the lens. This image is a kind of semiotic inheritance passed down from my “younger mother” onto me and perhaps onto our lineages to come.

This kind of image was also reflected back to me when I encountered Lebogang Tlhako’s work in the Reflections: On Black Girlhood exhibition at Market Photo Workshop.

Tlhako’s images arrest me with their sense of familiarity. In one of her inkjet prints on cotton stands a young girl returning the gaze of the camera: The young girl confidently stands with thick white-rimmed sunglasses, gold earrings with a matching purse and a bow on her dress’s clavicle.

This piece formed part of the Sibadala Sibancane collection, which is a linguistic play in isiZulu of being “old while young”. The series of photography explored in this collection spoke to the paradoxical nature of children in South Africa, often engaging in role-playing games and mimicking adulthood through activities such as playing house and dress-up.

However, this playful imitation reflects a deeper societal trend, where young individuals are compelled to adopt adult roles and responsibilities at an early age due to living circumstances.

These images are in conversation with the work of Haneem Christian, Ruth Motau, Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi and Motlhoki Nono under Danielle Bowler’s curatorial configuration of black girlhood. Bowler invites us into ephemeral depictions of young black girls with this exhibition.

This is a world of the “ordinary extraordinary”, as she writes in her curatorial missive, where black girls straddle inequality, shame, critique and yet, insistent joy and self-authorship. This exhibition is comprised of reflections on black girlhood from five contemporary South African artists across multiple generations.

The exhibition is an invitation from the general assumptions of black girlhood into the granular and specific, with themes of memory, biography, performance, the body, community, care and “being in public”, through creative practices of waywardness.

Photographic and video works by Ruth Motau and other artists

Photographic and video works by Ruth Motau and other artists

Reflections: On Black Girlhood is Bowler’s artistic response to the Sighting Black Girlhood course, a hybrid course taught across the universities of Johannesburg and Pennsylvania, which quite literally explored what it was to sight, cite and site black girlhood across South Africa, the USA and the Caribbean.

As with any artistic millennial worth their salt, Bowler is a talented multi-hyphenate. Having worked as an arts editor and journalist, musician and theatre maker, Bowler brought a wealth of expertise to her first curatorial endeavour.

“When I first entered [into the space], I was having a lot of conversations with different curators, and they were telling me how important writing is curatorially and that having that skill was a critical skill I was bringing to the practice already,” reflects Bowler over a Zoom call.

“I think that specifically being an arts writer is a discipline in which you are constantly thinking about some of the same things that you are thinking about curatorially … when I read that curating was about opening up a set of questions and not trying to establish a definitive set of closed answers, it really opened up a way of thinking about what this may offer me as another practice.”

Bowler’s scholarly and artistic practice configures itself in a relational dance where she is cognisant of the ethics of citation, located-ness and the deceptively simple act of seeing.

“I think I am always attracted to thinking with and thinking alongside,” she continues as she explains how she attended to questions of space, spacing and meaning-making in this exhibition.

Bowler’s theatre background helped to think through questions of staging and how every element of staging is an intentional statement about the artworks and their relationship and proximity to one another and how to animate this vast web of being. “There is a lot to think about, you’re thinking about the composition of the room and how that speaks to your thematics. You are thinking about colour and for a long time I was going through colour theory to understand what different colours represent.”

In her speech on the opening of the exhibition on 2 September, Bowler foregrounded the notion of feeling. Feeling, for Bowler, is a rigorous intellectual pursuit as she is currently busy with a PhD at the University of Johannesburg researching a “practice of feeling”.

“Something that I’ve been trying to think through in the PhD is what I’m calling ‘the practice of feeling’, and what does it mean to move via feeling, which you can substitute for feelings of empathy or empathy within that,” she offers in our interview. “As I said at the exhibition, every work was chosen because of feeling. As I looked at the works there was a specific act of being moved that determined my selections and that also determined the exhibition itself.”

I was overcome by a distinct feeling of unease on the opening night as I approached Thenjiwe Niki Nkosi’s newly commissioned and reimagined installation from her 2022 exhibition Chorus for Bowler’s exhibition.

A white spring floor reminiscent of a gymnasium sits at the edge of the room with a five-minute sound installation, which can be heard on the attached earphones. The instructions for this part of the exhibit read, “Please feel free to put on the headphones and stand, jump, walk, perform or just be on the spring floor while you listen.”

The reconfiguration of Nkosi’s gymnasium in this way was both enticing but also reviling as the menacing invitation to smile was heard on a loop through the earphones. The sound installation was made up of real excerpts from the commentators in US-born gymnast Gabby Douglas’s gymnastic competitions.

Douglas is a world-class gymnast who made history 12 years ago at the London Olympics as the first black gymnast ever to win the all-around gold — and four years later, winning the team gold in Rio as part of the final five.

“Smile, she looks so much better when she smiles,” plays on the earphones. This commentary, although directed at Douglas, is an unwelcome invitation most black femmes and girls have had to experience in their public lives.

Offering a smile can be a nebulous, fraught practice in a world riddled with misogyny and the consistent abandonment of black girls the world over. Despite my own dis-ease, the piece is, however, a curatorial success for Bowler as it invites meaning-making from each member of the audience, much like the nineteen other artworks on display.

This is quite a significant jump from the first iteration of this exhibition, which was held in Kingston, Jamaica at New Local Space. That group exhibition was titled Sighting Black Girlhood, featuring work by Camille Chedda, Tishana Fisher, Michaella Garrick, Sasha-Kay Nicole Hinds, Oneika Russell and Abigail Sweeney.

“In Lebogang Tlhako’s work I felt the connection between our two shows,” writes Chedda over email.

“In Jamaica we went about our project by first learning from our subject/muse and presenting them how they needed to be seen — as monuments, as being healed, or simply at rest.

“The young girl in Lebogang’s photo collages emulates her mother’s style and pose; she inserts herself into a space that has changed over time. We here created images and objects about these young women after absorbing their stories.”

It is clear that both Bowler and Chedda were able to tap into a global experience through highlighting the hyper-local in their presentations of black girlhood.

Through her tender practice of empathy, Bowler is able to sing “a black girl’s song”, as Ntozake Shange reminds us in her previously unpublished works. As the light bounces off each piece into a kind of reflection, Bowler reminds us to reflect on the inner worlds that shape the intimate lives of black girls here and across time and space.

Reflections: On Black Girlhood is showing until 31 October at the Market Photo Workshop.